This interview was first broadcast by the Christian Emergency Alliance as a podcast, a truncated version of which is republished here with kind permission.

Tat Stewart grew up in Iran as the son of Presbyterian medical missionaries, but when he left to train for ordination he had no plans to return, until he received a letter from the Evangelical Church of Iran in 1978, asking him to come back as pastor. When he and his wife, Patty, who also grew up in Iran, finally arrived back in Tehran, it was the summer of 1979 and the revolution, in Tat’s words, was in “full bloom”.

Arrival

We arrived in Iran in the summer of 1979. Just five months earlier, Ayatollah Khomeini had flown in on his Air France jet, for those who are old enough to remember these things.

And there was actually no government on the ground, there was no police force. When you drove somewhere, you just prayed you didn’t get into an accident, or do anything [else wrong], because, as a Westerner, you’d probably be guilty, no matter what happened.

We didn’t go out at night, because there was still shooting in the streets. Each neighbourhood was kind of controlled by its own vigilante group, because there was no police. You could hardly move from neighbourhood to neighbourhood at night, so we just stayed home. And we began to study the language and began to lead worship services for the remnant of what had been the Community Church of Tehran, which before the revolution had had over 600 members. And now, when I arrived, they had six members left.

So we began to minister there in Tehran, in the autumn of 1979.

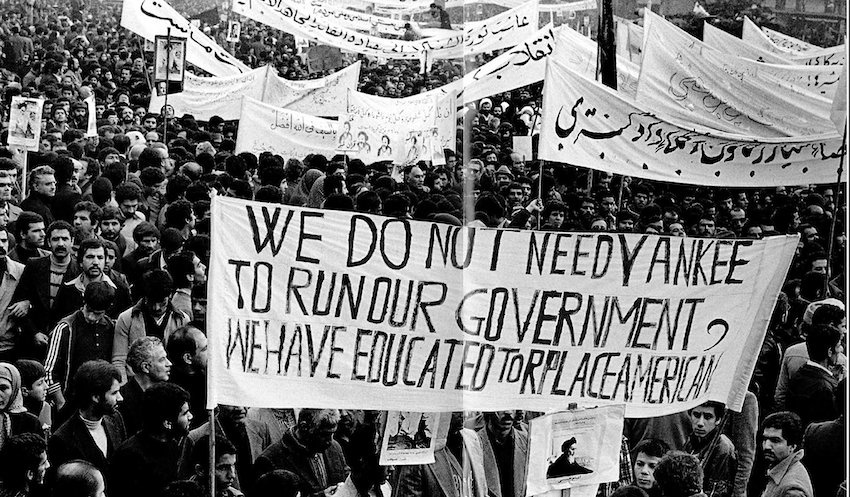

Anti-American sentiment

Tehran looked like a bombed-out city, because of all the demonstrations and burnings – many buildings were destroyed. A lot of construction had just stopped. Everywhere you looked, you saw buildings that were partially built.

And the mood of the Iranian people at that point was extremely anti-American. So, even when I would go into a grocery store to buy a few things, people looked at me with a sort of disdain, like: “What the heck are you doing here?”

What saved me, in many ways, was that I knew the language. So I would respond not in English, but in Farsi, and in some cases even Turkish, because a lot of the stores were run by the Turkish or the Azeri people. And that really helped.

But along with that stress was the tremendous turmoil that the Christian community was going through. Let’s remember a couple things: before the revolution, 55,000 Americans lived in Iran, and most of them lived in Tehran. At this point, there’s about 200 of us left!

The embassy is still there – it’s on a very small crew of people, but the embassy is still there – and the Christians of Iran, even when you add all of the groups, the Catholics and the Orthodox, are still less than 1% [of the population]. So we’re like a little drop in this sea of Islam.

Now, the society is divided between the poor and the low class, which have revolted against the wealthy and the rich. So the wealthy and the rich are now clinging to what they have, because every company went through a revolution – it wasn’t just the government. In every company, the workers took over. And in some cases, they just divvied up the merchandise and closed down the business.

There were a lot of levels of turmoil. And people said to me – even Iranian Christians said: “What are you doing here? Why are you here?” And I said, “Well, God called us to be here.”

When I went out on the streets, I was very conscious not only of what people thought, but also demonstrations would just crop up all of a sudden – and I got caught in one demonstration once, which was a scary time.

So we lived with a certain amount of fear. We listened to Voice of America and the BBC – we listened to news broadcasts twice a day to find out what was going on in our city, because there was no way for the Iranian media to figure out what was happening in the city.

And so you planned your day around demonstrations. Iranians have hundreds of celebrations of different martyrs, and things like that, and the whole city closes down, and everybody wears black and pours into the streets. And that’s not a day you want to go strolling in the park! So we lived with a certain amount of anxiety and fear.

Khomeini takes control

When we got there, all the different groups were expressing their opinions. If you’d go to the University of Tehran, you could buy any book. You could buy Bibles, you could buy communist literature; there was this total freedom, because there was no government crackdown, and so every kind of idea was going. And in some ways people saw it as kind of the glory days – you know, “The revolution has brought freedom; we can all express ourselves, in all the different groups.”

But Khomeini was a very shrewd leader. And what he did is he gave an opportunity for all of the different subgroups to show their hand, and then he organised a whole army of thugs, and they poured into the University of Tehran, and they beat up and closed down every other movement or group – just took all their literature and burned it, in the middle of the day.

We lived next to a large hospital, probably a couple miles from the University of Tehran, and all day long the ambulances were coming in, with people that had been beaten up, people that had been just terribly, terribly wounded. And from that point on, he [Khomeini] took over the revolution. From that point on, it was his work.

And then they engineered an election, that the people would elect the Islamic Republic of Iran. And there was only one place to vote: yes. And then you voted yes, and then your ID card was stamped to show you had voted. And so if you didn’t vote, you might never get a job; you might have different problems in the future.

So it was kind of a sham, but it was announced that the vast majority of people of Iran endorsed the Islamic Republic of Iran, and Khomeini became the final authority and power over everything.

Pastoring in the midst of it all

I worked with two churches, because the Iranian evangelical church was fearful of identifying with American missionaries because America was “the enemy”. So my title was pastor of the Community Church, which was the expatriate church and English-language church.

And basically that church, I put an ad in the only English-language newspaper – the only ad for a church in the whole country! – and we built up a congregation of about 60 people in a month or two. But they were people from all over the world – from Africa, from Japan, from Europe, from Australia; people from different embassies, who were Christians and who wanted to worship in English.

So that ministry was working with a small minority of people who were trying to figure out what’s going on in the city. After church, people hung around for maybe a couple hours just to learn: “Where do you get this?” “What happened there?” That kind of stuff. It was very, very interesting.

The other side of my ministry, which was the unofficial side, was that the senate of the Evangelical Church of Iran assigned me to be the advisor to the youth ministries of the denomination, and we had four churches in Tehran – two of them worshipped in Persian, one worshipped in Armenian, and one worshipped in Assyrian.

And I began to lead meetings, even though my Farsi was pretty basic, because I hadn’t been in Iran for 15 years.

American Embassy siege

There were very few Christian missionaries left in the country. From our mission, there were just two other couples. I knew of maybe four other missionary couples in the whole country.

And, remember, now we’re moving into the autumn, and on 4 November 1979, the American Embassy is run over by students.

And it was a Sunday. And the central church in Tehran wanted to worship on Sunday – Sunday is a working day in Iran, so they had a worship service at 6pm, so people could come from work and go to church.

So my wife and I, and the kids, drove to church, and we were hanging around before the church service, talking to people … and then word comes that the American Embassy has been run over. And we kind of yawned, because a few months earlier, in February of that year, it had been run over and the local police came and took care of it.

So we thought, “OK, it happened, and probably it should be OK.” And in fact, on the way home from church, we actually would have gone past the American Embassy, and I said: “Let’s just drop past the embassy and see what’s going on.”

But when we got to that area, the streets were all barricaded, so you couldn’t even get close to it.

So we didn’t really see anything, we went home, and of course we started listening to Voice of America or the BBC, and finding out that the American Embassy had been taken over. And, again, we thought: “This is temporary; it will pass.” But it didn’t.

So that began to change the scope and the climate that we were living in, because now the question was – other Americans were calling me and saying: “We don’t have an embassy to call on. Can you help us? What do you hear?” Because they knew I knew Persian; they knew I had more contact with the Iranian people. The fear of the other Americans walking the street was: “They’re going to grab me!” So that was not a good feeling.

But Ayatollah Khomeini came on the air and he said: “Look, our gripe is not with the American people; it’s with the American government. So please treat American citizens courteously.” And that was a great relief to hear that!

And at that time there was another kind of shake up of our family, because our mission said: “You know what, I think we should take the women and children out of the country for a while, just in case things get worse. So about a week after that, I sent my wife and two kids to London. I have a sister that lives in London, and they went to stay with her.

And I spent several weeks, which were really some of the hardest times of my life, being totally alone in our apartment in Tehran, and not having my family. And Christians were a little bit hesitant to relate to you, because I was known in my neighbourhood as “the American spy”. I mean, if you asked the people down the street, “Who’s your neighbour?” … “Well, he’s an American spy!” That’s who we were known as!

It’s interesting – not one Christian Iranian family in the year we were there invited us to their home for a meal, which is absolutely unheard of: Iranians are extremely hospitable. Only an Assyrian pastor who was not a Muslim convert invited us once to his home. So that was very strange.

It was a stressful time, and now my wife and kids were out of the country, and I went into kind of a deep depression one night, just sitting in the dark. The electricity would go out all the time, and I was hearing all the time: “Death to America! Death to Israel!”, and I really went into kind of a deep depression.

10 days to leave

After leading a youth conference in northern Tehran for 97 young people, in what was known as the “garden of evangelism”, Tat describes his shock at being told he has 10 days to leave Iran.

I was called in by the Islamic censorship bureau, and I went in and took a Jewish-Christian lawyer with me, just to have somebody with me. And [the official] said: “We’re asking you to leave the country in the next 10 days.”

And I was standing in front of this official of the government, and I said: “Is it OK if I just say something?”

And he hardly looked up, and he said: “What do you want to say?”

I said: “I’m just here to share the love of God with your people. I’m not here on the behalf of the American government; I’m here on behalf of Christians in America. And my God tells me to obey authorities, so I want you to know that I will follow your orders, and we will leave, even though we don’t want to, because we love this country, and we love your people.”

Well, I was impressed with what I said, but apparently he wasn’t all that impressed!

So we had 10 days to leave. Now, imagine being told you have 10 days to close a church, deal with a car and property, a congregation… But one of the things, of course, was we told the English-language church, and we had Communion together, and we just shut down the church and said: “Worship at Iranian churches if you can.”

And the Iranian Church didn’t want to make a big to-do out of it, because we were Americans, and they kind of were “hush-hush”.

The morning we were supposed to leave, we were supposed to be at the airport at 4am – you needed to be at the airport four hours before your flight, just because of the chaos at the airport.

Imagine: everybody that had anything to do with the Shah is trying to get out of Iran! Imagine trying to get airline tickets within a week in such an environment! When I came out of the office, I stood there and said: “What am I gonna do?”

Departure

Tat’s family eventually secure tickets home thanks to the Swiss ambassador, who contacts Swiss Air on their behalf. Seven days later, they arrive at the airport early in the morning.

The day arrived, and we arrived at the airport at 4am, and when we got there, there was a crowd of 30 people who gathered around our car. And at first I couldn’t see who they were. And I thought, “Oh, boy, we’re not going to get out of here!”

But it turns out it was all the young people of the church; they had been praying and fasting all night long at the airport. And they picked up our bags, they picked up our kids, and I felt like one of these mafia guys, with all these big guys surrounding you and walking you through the airport, like: “Get out of the way! Here we come!”

The airport was chaotic, because people were not allowed to take rugs out, they were only allowed to take $1,000 worth of cash out. People were trying to smuggle things out. There was yelling, there was screaming. It was a chaotic airport. How we got through that airport God only knows.

And we were delayed a little bit by the Pasdaran [Revolutionary Guard], who put us in a special room and searched our computers, trying to find stuff on us. And they were Turks, so they were talking Azerbaijani Turkish together, and they didn’t know that I was understanding everything they were saying!

And they kept saying: “These guys, they must have done something wrong; we gotta find something!” They were probably trying to get some money from me.

So finally we pass all that … and we got to the gate, and then on the loud speaker comes: “Would the Stewart family please come up to the podium?”

And, again, your heart sinks.

And the guy says: “We have a little bit of a problem.”

And I said: “What is it?”

And he said, “Well, we’re gonna have to put you in first class, I hope that’ll be OK!”

It’s like God just bumped us up to first-class! And then we flew to Zurich, and then we came back to America.

When we got off the plane at Kennedy Airport, my son, who was six years old, said: “Daddy, look, there’s an American flag that’s not burning!” He had never seen an American flag that was not burning, and he was quite impressed with that.

So that was a one-year experience, but certainly a life-changing experience for me.

You can listen to the whole of Tat’s interview, including his reflections on the startling growth of the Church in Iran, by listening to the podcast.

0 Comments