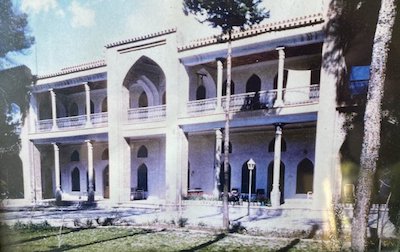

The bishop’s house in Isfahan – once the seat of the Anglican Church in Iran – was confiscated by an Islamic Revolutionary Court judge on 6 November 1979, nine months after the revolution that brought Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to power at the head of a new Islamic Republic.

In all the years since, the house has stood empty and unused. Until now.

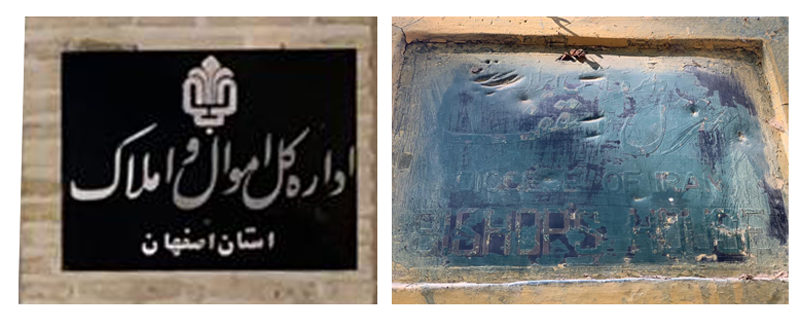

Over the past two years, the Mostazafan Foundation, an organisation directly ruled by the Supreme Leader and which purportedly works to support the poor – “mostazafan” literally translates as “oppressed” – has restored and now reopened the bishop’s house as an office to manage its many other properties.

(It should be noted that the Mostazafan Foundation is one of the richest organisations in the country – with an estimated value of over $3 billion dollars – and that its dealings are far from transparent.)

The plaque which once bore the title of the Bishop of Iran has been replaced with that of the foundation. Its logo is there for all to see.

And this month, for Muharram, the Shia month of mourning, a banner has been erected in front of the house, declaring it house “a house of mourning for Hussein”, the murdered grandson of Muhammad, and sporting photographs of both Khomeini and his successor as Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei.

Why was it confiscated?

“Seldom in history can it have been that suspicion, misunderstanding, fanaticism and cupidity have struck an innocent group of people in the way they have struck the tiny Episcopal Church in Iran under the Islamic Revolution.”

These were the words of the first ethnic Persian Anglican bishop of Iran, Hassan Dehqani-Tafti, in his 1981 book, “The Hard Awakening”, as he reflected upon all that had happened in a bewildering first few months after the revolution.

The bishop left his homeland on 2 November 1979, just four days before the confiscation of his home, and a week after surviving an assassination attempt.

In the preceding nine months, everything that had been established over decades by missionaries had been turned upside down.

It began with the murder of the Anglican priest in Shiraz, Arastoo Sayyah, just eight days after Khomeini’s arrival in Tehran.

Then followed a wave of confiscations of properties, beginning with the hospitals in Isfahan and Shiraz in June and July 1979 and culminating in the confiscation of the bishop’s house on 6 November.

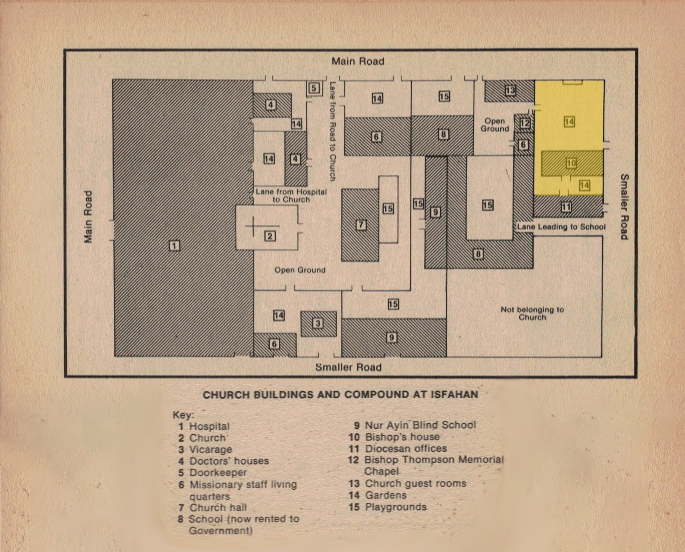

The first assault on the bishop’s house – a large property in Isfahan within a compound that also hosted a church and Christian-run hospital, school and centre for the blind – came on 29 August 1979, as a group of men the bishop described as “ruffianly but obviously highly organised” burst into his home and ransacked it, before setting fire to many files and personal documents, including family photographs.

Six weeks later, on 8 October, the bishop was arrested because he refused to hand over access to the church’s funds. Later that month, on 26 October, as he continued to refuse to give in to the demands, an attempt was made on his life as he lay in bed with his wife Margaret, such that, when a week later he left Iran for a conference, friends encouraged him not to return. And indeed, the bishop never did.

‘Insult to Jesus Christ’

On the confiscation order, dated 6 November 1979, an Islamic Revolutionary Court judge linked the confiscation to that of the hospital within the same compound five months earlier, saying that, according to unspecified “evidence”, it had been “built using the money belonging to the oppressed Muslim people to be used for the benefit of the imperialists” and “to poison people with their propaganda”.

The judge, who was later disgraced and executed, said the activities of those running the hospital had been “not only an insult to Jesus Christ (peace be upon him), but has also become a centre for anti-Islamic activities”.

“According to the evidence, and sufficient reasons,” the judge continued, without providing any details, “this hospital, before being a medical centre, was a place to lead ignorant Muslims astray, with all kinds of propaganda to deter us from the light of faith, and lead us to blasphemy and spying.”

Such fantastical claims were also made in the weeks and months after the bishop’s departure, as a slew of articles appeared in an Iranian magazine, accusing Anglican church members of things the bishop said read “more like James Bond thrillers”, including connections with the CIA and British Intelligence.

In the months that followed, the bishop’s only son, Bahram, was murdered and an attempt was also made on the life of the bishop’s former secretary, while other church leaders were rounded up and arrested.

‘I hope and believe we will see justice done’

Now, 41 years after the first attack on the bishop’s house, its gradual expropriation is finally complete.

The only parts of the compound that still belong to the Anglican Church are a few apartments and a church (St Luke’s) suffocated of all possibility of growth, as new members are not permitted.

“I hope and believe that once things are settled in our country, once the fever of unreasonableness cools down, we shall see justice done,” the bishop wrote in his book, but today that justice seems farther away than ever.

Yet, even so, the self-acknowledged “tiny” church the bishop left behind has experienced startling growth.

From just a few thousand Persian Christians at the start of the revolution, there are now as many as a million converts in Iran, according to new research.

But the faith they practise must be practised in secret, as they are not permitted to attend church services, and as a result they face the constant threat of arrest and imprisonment.

As the bishop wrote all those years ago, “the persecution of church members and the illegal confiscation of church properties started in the first week of the Revolution and still continues relentlessly”.

The same could have been written today.

Reacting to the news, the bishop’s daughter, Guli, who is now herself a bishop in the Church of England, told Article18: “I had a very happy childhood in the Bishop’s House, which was my home and where I spent my formative years. I have countless memories of so many people who passed through the doors – colleagues of my father, friends and many, many guests.

“My parents were very hospitable. When we left and the house was confiscated, it still included all our belongings – other than those we had taken in one suitcase each.

“In the last few months it was the scene of unhappy events such as a raid and the attack on my father’s life.

“The house, which belonged to the church, was unlawfully confiscated and the injustice of that still stings. However, after 41 years of being vacant, I hope it will now at least be put to good use and that it will truly be used as a place from which those who are dispossessed and poor may be helped.”

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks