Introduction

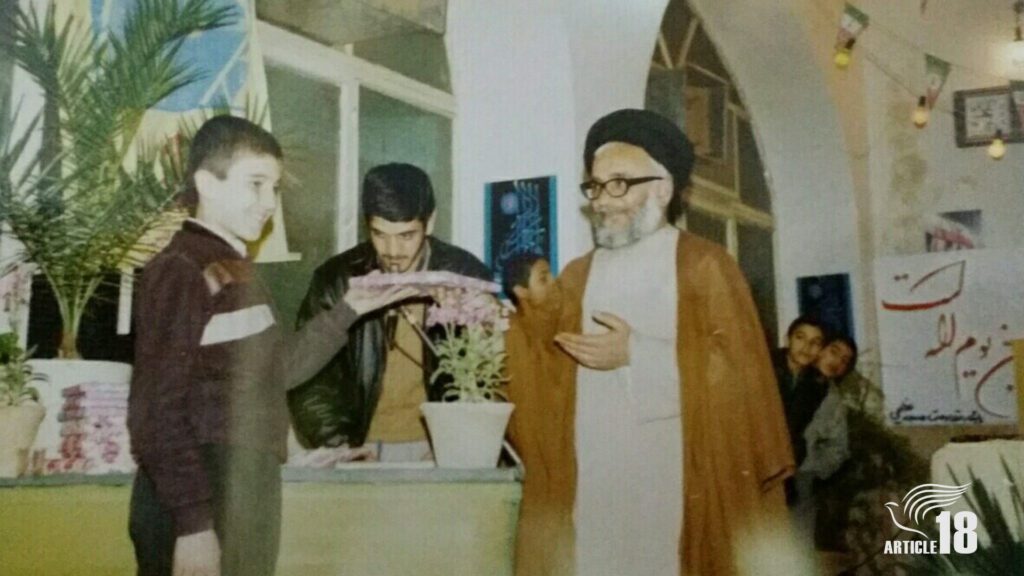

- My name is Alireza Aghajari. I was born in June 1979 to a Muslim family in Shiraz and became acquainted with Islam and its religious practices at the age of 10. From the age of 13 until I became a Christian, I tried to always attend congregational prayers in the mosque. At the age of 16, I took a Quran recitation course at our local mosque, run by the Shiraz Islamic Propaganda Organisation. After receiving my coaching certificate, I became a Quran instructor at the mosque and elsewhere. I could also recite many chapters of the Quran by heart, and for this reason I received awards and plaques of appreciation from the mosque. At the age of 17 or 18, with a few of my friends, I founded one committee named after the last of the Twelve Shia Imams, Mahdi.

- I had a friend from childhood who was older than me and had volunteered to go to the front during the Iran-Iraq War, when he was 17. One of his brothers was killed in the Iran-Iraq war, and his other brother was a seminary and university professor and also the Supreme Leader’s representative in the Hajj and Pilgrimage Organisation. But one day in 2003 I noticed that my friend hadn’t been to the mosque for some time, and I went to his house to inquire about his well-being and the reason for his absence. During subsequent visits, he talked to me about his conversion to Christianity and I asked him for a copy of the Bible, intending to read it, then prove to him with evidence and reasoning that he was on the wrong path.

- I read through the entire Bible, but I had been taught in Islamic thinking that it had been distorted. My friend stood firm and insisted on his Christian beliefs, and it was strange to me that someone who had fought to protect the country, was a religious teacher, and who I always saw at the mosque, had now become a Christian. But at the same time, I witnessed many positive changes in my friend’s behaviour, and because of that I became curious to undertake further serious research about different religions.

- With the mindset that I didn’t want a religion that was only inherited from my parents, I consciously emptied myself of my previous beliefs and acted as though I had come to Earth from another planet and was doing research, so that I could ultimately follow and adopt whatever I found to be the right path as a result of my research. In this endeavour, I even stopped praying.

- The first religion I researched was Islam. I studied the Quran in the Persian translation and various commentaries. To find answers to my questions, I would go to the office of Grand Ayatollah Makarem Shirazi and talk to the person in charge. Meanwhile, I borrowed a copy of the Torah from a friend of mine who went to the local synagogue, and studied it. I also looked into the beliefs of other faiths, such as Nimatullahi dervishes, and read the Nahj al-balagha sermons. My father was very interested in the Nimatullahi group, attended their gatherings, and had an official mentor there who taught him about the faith. I also attended their ceremonies as part of my research and witnessed many strange things. I also went to the Zoroastrian Association on Zand Street in Shiraz to learn more about Zoroastrianism, and when I came out, an agent from the Ministry of Intelligence [MOIS] got out of a car and asked me why I had gone there. I explained to him that I had come to conduct research about Zoroastrianism, and it was then that I realised that such places were under the control of agents from the MOIS and that they were checking everyone’s movements.

- The Zoroastrian Association, synagogue, Church of Simon the Zealot, and Shiraz Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] base were all close to each other, and security officers could therefore easily monitor them with cameras.

- I also read the works of [philosophers] Osho and Friedrich Nietzsche, and looked into mysticism. But a special feeling in my heart urged me to re-read the Bible that I had previously cast aside. And this time I studied it seriously, and many verses illuminated my mind like a light.

- After this, I asked my converted friend to let me attend one of his house-church meetings, and one Tuesday I attended for the first time. There were about 13 people there, and what caught my attention was the style of worship and songs, to the point that I asked for a copy of the worship CD, and they provided me not only with that, but also audio files of several teaching lessons on the Christian faith, and I listened to them about four times.

- When I attended the church for a second time, I came with about 100 questions, which I had written down, and they patiently answered me. At the time, their answers didn’t fully convince me, but I decided to keep looking into Christianity by carrying on attending the meetings.

- By early 2005, I had almost completed my research, but I was still torn between all the different religions, and especially between Islam and Christianity. However, eventually, after a personal spiritual experience on 5 April 2005, I formally prayed for salvation in the house-church meeting and became a follower of Christ. Because of my great interest in the Bible, I read the entire New Testament every week, and studying the Bible and experiencing Christ brought about profound changes in my thoughts, actions, and relationships. I had also suffered with severe asthma for a long time, and took tablets and inhalers to manage my symptoms, but I was completely healed from this condition, I believe, as a result of my prayers and those of other church members. Still, it took about two years for me to completely break away from my past beliefs.

Working for the IRGC

- The IRGC had two departments: the “Intelligence Protection Division”, and “Intelligence Unit”. The Intelligence Protection Division was responsible for internal affairs, while the Intelligence Unit was responsible for external operations. The IRGC in Shiraz had about 10 “Resistance Areas” belonging to the Basij [paramilitary group], and each area had an intelligence protection officer. My role with the IRGC was to handle and monitor behavioural issues or other problems in mosques, as well as people’s movements, and administrative and archival matters.

- Because I continued to dress in a so-called “Islamic” style – that is, with a beard and untucked shirt – some church members couldn’t fully accept or trust me and were afraid of my participating in the meetings. Sometimes they even changed the time and place of the meetings and didn’t inform me. Meanwhile, those who had more trust in me prayed for a change in my work situation. Every time I wanted to attend the meetings, I would discuss it with my friend, who trusted me and who would coordinate with the church pastor so that I would be allowed to attend. Eventually, under new leaders, I was accepted as a member.

- In March 2006, the IRGC informed me that according to new regulations regarding employment with the IRGC, a high school diploma was no longer sufficient and I needed to continue my education. I was extremely happy to be able to use such an opportunity to end my career with the IRGC, but I tried not to show it. After the Nowruz holidays, I told them only that I didn’t intend to continue my education and wanted to take care of my family. I explained that since I was the eldest child of the family, I had been working since I was 10 years old and had helped to cover the household expenses. Besides, my father had had a stroke and was at home and sick.

- After leaving the IRGC, I worked as a driver for a while, until I got a job at a small printing house. After four months, several of my colleagues at that printing house came to faith in Jesus Christ, and we held house-church meetings there every Tuesday.

House-church

- One of our Christian activities was to meet with seekers and converts who had contacted one of the Christian satellite networks. We would meet and talk with them in public places like parks for a few months and then, if we found the person trustworthy, we would allow them to attend the house-church. In addition to this, if new people who were relatives or friends of members wanted to attend, we would generally meet them privately and separately first. Due to the possibility of arrest, attending these meetings was always accompanied by additional security precautions. For example, we had strict regulations regarding mobile phones, or how we organised the day and place of meetings. Another service we provided, which we carried out with great caution, was to send Bibles, Gospels, and a film of the biography of Jesus Christ to people who had requested it from one of the Christian satellite networks. People from different cities and villages of Iran would request these things, and we would send them.

- Evangelism also had a special place in our church, and we did it with care, sensitivity, commitment, and prayer and fasting. Our activities reached a point where we served 11 churches in Shiraz, each of which had around eight members. For security, the groups didn’t know each other, so that if one group was in danger, the others would be safe. All members adhered to safety precautions. If someone failed in this regard, we would deal with them seriously and consider disciplinary measures such as temporarily prohibiting them from participating in church activities.

- Sometimes, to learn theology and strengthen our personal faith, we attended Christian conferences outside Iran and got to know some of the other leaders. But even when we saw each other on the streets of Shiraz, we would pass each other like strangers, because we knew that if someone ever got arrested by the MOIS, it would be better for the safety of our groups and other Christians not to have information about each other. We had established most of these security tips based on our personal experiences.

- To communicate with other leaders we thought may be being monitored, we followed digital security tips. For example, we went to different Internet cafes every time, and first checked the settings to make sure that our activities wouldn’t be saved on the computer’s hard drive. We also made sure to use secure sites, and if we wanted to communicate at home, we installed programs that had the ability to completely and securely erase information. We also entered our passwords by using the mouse instead of the keyboard. All of these measures allowed many people to be protected from harm by the intelligence agencies of the Islamic Republic.

- My wife and I, along with three other fellow Christian converts, served our 11 churches. Due to the increase in our activities, we selected individuals from among the church members who were eager to serve, and formed two groups of leaders with various responsibilities. We assumed supervisory responsibility and, without members of the various churches knowing our identities, would attend their meetings irregularly as guests or volunteers. Some thought we were researching Christianity. These measures meant that if the intelligence agents later arrested us, they would be unaware of the existence of the other groups and would only know the names of those we had been arrested with.

- Our activities included preparing worship songbooks, books on the Christian faith, and other resources essential for all the churches for their worship services and the growth of their faith. After preparing them, we would provide these resources to the churches. Not all families had access to satellite TV, so we tried to feed the churches with various resources in any way we could.

Arrest

- Most Iranian converts are very excited when they come to faith in Jesus Christ and are eager to talk to others about their Christian faith. Heydar* was one of our good brothers in the church, who had previously studied at an Islamic seminary to become an Islamic scholar. His aunt’s husband had been appointed to a special position by Ali Khamenei, the leader of the Islamic Republic, and his brothers also served in the institutions of the Islamic regime. He had gone to Mashhad for a while and then joined a Sufi school. Finally, after hearing the good news of the gospel, he had come to faith in Jesus Christ. We met him in the park for six months, and then he joined our house-church meetings. One night, during the Shiite religious mourning period, he went to one of the largest Husseiniyas [Shia gatherings] in Shiraz, without consulting his leader, and placed 384 Christian pamphlets called “Letter from the Father” next to the prayer mats of the attendees. As soon as he left the Husseiniya, he was arrested. He was put under a lot of pressure from both his family members and the interrogators, and since he had converted only recently, he accepted the intelligence agency’s offer to cooperate with them and was released that same day.

- About a month later, on 21 June 2009, in coordination with the IRGC, after entering the building where the house-church meeting was being held that day, he left the door open for the officers to enter. Shortly after, the officers arrested all the members present, including women, men, and even the children, who were between the ages of one and 12. The children were extremely scared, and even the one-year-old, who was the grandson of one of the members, was kept in detention until the next morning.

- That day, one of the four main leaders of our church network, Brother Mehrdad*, was among those arrested, having come to supervise our meeting. After being arrested, he was taken, blindfolded, to the middle of nowhere and, in the dark, they removed his blindfold, put a gun to his head, and threatened to kill him. He had a heart condition, and his condition deteriorated following this incident.

- The intelligence officers contacted the families of the single ladies who had attended the meeting, and the husbands of the married women, and told them: “We have arrested these people for having illicit relations.” Some of the fathers of the unmarried women, influenced by the false and insulting insinuations of the intelligence officers, had beaten their daughters in the presence of the security officers. The intelligence agents had then released all of them on the condition that they return to the intelligence office whenever summoned.

- I didn’t attend the meeting that day, but one of the relatives of the arrested people came to our home and informed us about the incident. After that, we took all the resources and books in our possession to the roof of our building and hid them in the air conditioning unit. Then I called Babak, another of the main leaders of our churches, but it turned out that he had also been arrested. Just 20 minutes before I had called, agents had arrested him with about 100 Christian CDs. Apparently, one of the members who had been arrested at the meeting, under great pressure and anxiety, had informed the interrogators about Babak’s activities and where he lived. We went to Babak’s home to comfort his mother.

- On Saturday 11 July 2009, my wife and I were getting ready to go to my cousin’s wedding and a lady from church named Maryam* had come to our home to do my wife’s makeup. At 5pm, the doorbell rang and someone called out my name, claiming to have brought a letter for me from the post office. But since we knew the post office’s closing time was 2pm, we realised that these people were from the security forces and that they had come to arrest us, and we didn’t open the door. In those precious seconds, we hid the flash cards that we had prepared for a marriage seminar, which also contained some photographs of the seminar, in the washing powder.

- Meanwhile, officers from the IRGC had rung the doorbell of our landlord, who lived downstairs, pushed his son, entered their yard, climbed the ladder on the side of our building, entered our terrace, and come into our home through the window. The officers, who were very big men, separated my wife and me and said we weren’t allowed to talk to each other.

- The way the IRGC act is very different from the MOIS. IRGC agents go to homes without a legal warrant and arrest people. They say obscene and offensive things and insult and humiliate them. When I asked them what permission they had to enter our home, they opened a folder and showed me a sheet of paper without any signature or stamp. They didn’t even give me a chance to read what they had written, just saying: “We have a permit and it’s none of your business.”

- One of the agents first asked my name and then asked if I was a Christian. After hearing my affirmation, he ordered a search of our home. They confiscated my computer, camera, mobile phone, crucifix necklace and even a night lamp in the shape of a cross. Mehrdad’s laptop was also at our place, and they also confiscated this, and then I had to sign a piece of paper upon which was written a list of the items they were taking.

- About 200 IRGC video clips, related to the nomads of Fars province, were in my house, because the IRGC Intelligence Protection Division had asked me to convert them into DVDs. They took these too, and after my release from prison, when I contacted the IRGC department responsible for monitoring nomads, I discovered that they had been contacted by IRGC intelligence on the day of my arrest and asked about the DVDs. When they had asked why, those who arrested me falsely told them that they had confiscated about 3,000 pornographic films from our home. I had to explain to them that what the security officers had said was completely false and that I had only converted to Christianity, and that was the reason for my arrest.

- I knew I was going to be detained for a long time, so I took off the suit I had planned to wear to the wedding and put on some more comfortable clothes and sliders. I also left my wallet at home.

- At first, they wanted to let our friend, Maryam, go, but when they realised that her husband, Davood, was active at the church and was one of those they had been looking for, they arrested all three of us. The agents had brought three cars with them: a Paykan, Peugeot, and a Samand. They blindfolded me and made me lie down on the backseat of one of these cars. What happened to my wife is in itself a long story that she may prefer to share another time.

- They took us to a place, which I later realised during my interrogations was a former water silo that belonged to the Quranic Centre of the Shiraz Basijis, and my brother had even gone there previously to recite the Quran.

- After arresting us, they also arrested our friend Adel at his shop, and went to his home to take his computer to be examined. They also called Davood and said that his wife had had an accident and was in hospital. After calling the hospital, Davood realised that he had been lied to, so he came to our house and, after talking to the landlord’s son, learned about our arrest. He quickly went home and emptied the large storage room of their home of Christian books and CDs. Then he called back the person who had called him about his wife’s “accident” and asked where he needed to go. He and his brother, who worked for the MOIS, then went to the address given, and Davood was arrested too.

Detention and solitary cell

- Maryam and my wife were kept, blindfolded, in a cell on the upper floor, which was actually a bathroom, for hours. But after initial interrogations, they were released the same night. However, Maryam was arrested again the next morning and held in an IRGC cell for about four or five days. She was later released on bail of 50 million tomans [equivalent to $50,000], and freed until her court date.

- They took me to a dark cell measuring about 1.10m x 2m. The cell had no lights. There was only one light at the end of the corridor in what looked like a very old building. When the call to prayer sounded, it was played very loudly and the speaker would send out these awful screeching sounds, which tortured us.

- I had three blankets in my cell, all of which were covered with long female hair. I was cleaning the blankets when I saw through the opening in the door that they had brought in another prisoner. It was Davood, and he was placed in the cell opposite. After a few minutes, they brought another person and took him to another cell, and I realised from his sandals that it was Adel. Then, at around 11pm, Babak, who had been taken for interrogation, was put in the cell to the left of mine.

- We were arrested in the summer, and the air inside the cell was very hot. They gave each of us an empty 1.5 litre bottle as our quota of drinking water for the day, and every morning we would give them the bottles so they could be refilled.

- The door of the cell was metal and they gave us our food and water through a small opening in the door. For breakfast, we were given a palm-sized piece of bread, a slice of cheese, and half a tomato. For lunch, we were given potato-cake sandwiches, and dinner was often burgers that didn’t taste at all fresh. We eventually realised that the burgers were made from leftovers from the previous days. After our release, we learned that our families brought us food, juice, nuts, and even clothes as soon as they learned about our detention. However, although the officers received these items, they didn’t ever give them to us, even after our release.

- There was no toilet or shower in the cell. Three times a day we were allowed to go to the toilet, which was located in the basement, accompanied by the guard. First, I would be blindfolded and couldn’t see whether the guard was armed or not. When he opened the cell door, I had to stand facing the wall so that he could blindfold me. Then, when I came out of my cell, he told me to feel the ground with my foot to find my sliders, but actually I used to find them by looking underneath the gap at the bottom of my blindfold. Then I held onto the wall with my left hand in order to find my way to the toilet, and I returned to the cell in the same way. In the toilet, there was an air vent through which we could glimpse the sky and so determine the approximate time of day, but we weren’t allowed to stay in the toilet for long. The guard kept knocking on the door to hurry us along and, due to this time limit, we felt under great physical pressure.

Interrogations and torture

- At around midnight, a guard finally came to take me to the interrogation room on the second floor, where the library used to be. The cells and interrogation rooms of this detention centre had recently been built. There were many stairs leading up to the interrogation area, and we were taken there blindfolded. The guards usually guided us with compassion along the way so that we knew when to take a step. For example, they told me when to lift my leg or when to bow my head. But when the intelligence agents took us for interrogation, they deliberately didn’t explain these things, and because of this, our feet would hit the stairs and our toes, head, and shoulders would repeatedly bump into the door and walls, causing us injuries.

- At first, they made me sit on a chair and left me there, while outside I could hear the constant beeping of car horns. Then, after a while, they took me to another room and made me sit on another chair. Then the guard came and said we had to go to the floor above, and I was told to take off my sliders. When we arrived, I saw from under my blindfold that some sheets of paper and CDs that they had confiscated from Babak’s house were scattered on the floor. There was also a photo of a Satanist ceremony, where someone was playing the keyboard and someone else held a bowl of blood. Again, the guard ordered me to sit.

- Then an interrogator came and asked my name. I replied: “I’m Alireza.” He replied: “Your name is Saeed.” Saeed was my alias, and how church members knew me. I insisted that my name was Alireza, but the interrogator didn’t give up, saying: “I know your name is Alireza, but the name under which you are active is Saeed.” I said: “If some people like to call me Saeed, I don’t have a problem with it. But my name is Alireza, and everyone knows me by that name. Even when you came to our home and asked if my name was Ali, I confirmed it.” During the first interrogation, I tried not to give them information and didn’t answer their questions. The interrogator said: “It seems you still don’t realise where you are. This isn’t your home!”

- Then the interrogator asked: “How many times have you been abroad, who did you go with and who did you see there?” I didn’t give him any information and said that I didn’t know anyone. He continued by asking how many church groups I led or was active in, but I evaded all the questions that night and didn’t provide them with any information.

- A few minutes passed and then they turned on the air conditioner. At first it was on a gentle setting, but then they turned it up. It was summer and I thought to myself: “How great! They turned on the air conditioner for me and now I am cooling down!” But after a while they poured a bucket of iced water on me and beat me with a stick. They mostly hit me on my neck and face, where I would feel the most pain.

- They beat me so much that I fell off my chair, and felt very unwell, started coughing and even had a panic attack. Then another intelligence agent entered the room and said that that was “enough for tonight”, and ordered the guard to take me to the bathroom. When I got there, I vomited, and after seeing my condition, the interrogator ordered me to be taken back to my cell. On the way back, the guard who was guiding me asked me how I was. When I answered, Babak heard me and recognised my voice, and that was how he discovered that I was in the cell next to him.

- It was well past midnight when Babak knocked on my cell wall and asked what information I had told the interrogator during my interrogation. I could hear his voice from the gap underneath the cell door. I told him that I hadn’t said anything. Babak said: “I gave them incorrect answers about a number of things and I want to make sure we don’t contradict each other.” For example, our senior leader was tall and his wife was short, but Babak had said that our leader was short and his wife tall. He had also not mentioned the names of the Iranian pastors and leaders who had attended Christian conferences abroad. He only said that a Christian woman whom we had met on the Internet had invited us to a seminar abroad to learn about Christian theology and that several Christian leaders had come from Mexico and England and taught us, with someone translating for them.

- Because we were always blindfolded, I still didn’t really have an idea of the layout of where we were being detained and how they were monitoring us, but it was clear that the guard wasn’t always there, and when he came, we could hear his footsteps and we would stop talking. Then, when he left, we would talk quietly so no-one else could hear us. In this way, Adel and Davood also realised that we were all being detained in the same place and we all agreed to only say the names of those whom we knew had been arrested alongside us.

- On the second night, I was taken for interrogation again and this time I answered some of the interrogators’ questions, in the way I had agreed with Babak, but in a half-hearted manner so as not to arouse suspicion. They hit my palms with a hose and asked me to give them the address of Iman, who served under the pseudonym “Sam”. But no matter how many times they hit me, I said that I didn’t know any “Sam”. The interrogator asked: “Who do you know?” I replied that I only knew Babak, Adel, Davood, and Mehrdad: that is, the names of those who had been arrested. Then the interrogator softened his behaviour as he repeated the questions from the previous day. Finally, they took me back to the cell.

- On the fourth or fifth day of my detention, a new guard came. He was kinder than the others, and gave us a broom to sweep our cell, telling us: “Sweep your cell and throw the rubbish out from under the door so that I can pick it up.” The other guards didn’t behave like that. Most of them had come from other cities and had been told that we were dangerous prisoners. They even seemed afraid of us. One time, we heard the nice guard talking to his colleagues, telling them: “These Christian prisoners are quiet and humble. But the Satanists or other prisoners cause a lot of trouble.”

- The floor of my cell was very dirty. After a few days, I was coughing violently and had to wipe my mouth with my clothes. Because the cell was dark, I hadn’t noticed that there was blood on my vest. It was only when I went to the bathroom that I realised that what had come out of my mouth was blood.

- The interrogators at the detention centre smoked a lot, which added to the intensity of my coughing during the interrogations. My coughing became so severe that one night the interrogator said he would call the emergency services. They even told me that the emergency services would arrive soon. But it turned out that they were lying. A few days later, by which time my vest was covered in blood, they took me for interrogation and when the interrogator saw my condition, he seemed scared as he asked me: “Are you unwell?” I said that it appeared so. The interrogator sent me back to my cell and a few minutes later they took me to the IRGC hospital, Moslemin Hospital, in a Paykan car. Interestingly this hospital is located behind the Anglican Church of Simon the Zealot in Shiraz and was founded by Christian missionaries and was known as the Morsalin [Missionary] Hospital until the 1979 revolution.

- One of the officers who accompanied me was a close friend of my brother, who came to our house regularly and ate with us. We were so close that he called my mother “aunt”. I had heard his voice once in the interrogation room and told him I knew it was him, but he had denied it. This time I saw his face, because I wasn’t blindfolded in the hospital, but he didn’t want to communicate with me, and I didn’t say his name again.

- It was night-time when they took me to the hospital. We went to the night ward, where a general practitioner was sitting with a surgical mask over his nose and mouth. I don’t know what they had told him, but he seemed very scared. I think he thought I had tuberculosis. When he asked me what was wrong, I explained that I sweated a lot at night, coughed incessantly, and that there was blood in my spit. He asked about my education and whether I had any medical knowledge. I think he wanted to know if I was lying! It was as if he wanted to know if I knew the symptoms of tuberculosis and whether perhaps I had said these things deliberately to make my situation seem more serious and urgent. Finally, he said that I had given myself a sore throat by coughing too violently and prescribed some medicine, which consisted of a white capsule and a very small blue tablet. Every time I took the tablets, I fell asleep.

- One day my sleep went on for so long that my friends banged on their cell doors so the guard would come and check if I was alive! After that, every time they gave me pills, I put them in my pocket, and when I went to the bathroom, I would throw them in the toilet or rub them on the wall until they turned into powder. I concluded that the pills were sedatives. Meanwhile, my health condition remained critical, and when I was eventually released, all my clothes were covered in blood.

- They would often take us for interrogation after dinner, around 9 or 10pm. But about a week after my arrest, the interrogations stopped and for about a week they didn’t take us for any more interrogations. Then, after that week, one day I heard the sound of the chief interrogator’s Samand car – the fan on his car had a problem, so it was recognisable. This sound had a bad psychological effect on me, because when I heard it, I knew the interrogator was coming to the detention centre. The impact on my nerves was so great that for years after my release, I would be afraid whenever I heard a car that had a problem with its fan, because it felt like at any moment they would come to take me back for interrogations.

- When he called me in again, the interrogator said: “We wanted to send you to Evin Prison in Tehran a week ago, but something happened there that prevented us from transferring you.” They were looking to see if we were connected to an organisation or church outside Iran, but fortunately they didn’t find any evidence.

- Then they listed about 300 names and asked me which of them I knew. I didn’t know some of the names at all, but I did know some of them. However, I said that I didn’t know of them, except for a few who had been members of Narcotics Anonymous (NA) before coming to faith. They asked me about these people over and over again, and I had to remember each time what story I’d told about each of them.

- On the first night, Babak had told me that if they asked about the leaders of Tehran or groups in other cities, I should say I had no information and that they should ask Babak, and I did as he suggested. I also realised that the interrogators didn’t have access to much information about our groups in Yazd, Isfahan, and other places, and that they had concluded that we weren’t connected to any organisation abroad.

- One of the female church members who was arrested around 10 days after us had written in her notebook the details of our Christian marriage seminar. For example, she had written: “First session: teacher Brother Ali”; “second session: teacher Brother Hamid”, and so on. Unfortunately, she had her notebook with her on the night of her arrest. So one day the interrogator asked me: “So what’s the story of the marriage seminar in the north of the country?” I explained to him: “You know that the situation is such that many girls and boys are falling into sin. So we gather single girls and boys and tell them about marriage and holy living. As for the conference in the north, it was only a recreational trip to give everyone a rest.” But my explanation that the topics we discussed weren’t anything special didn’t convince him.

- Sometimes the interrogator would say: “Lift your blindfold a little and read what you wrote and explain what you wrote.” Finally, he said: “You are either very stupid, or you have been taught how to speak during interrogations!”

- By arresting a few of us, they had achieved their goal and regained the trust of the city’s Security Council after what had happened in the Husseiniya. On the day of that incident, high-ranking officials had been present, so it could have been a great disgrace for them. But our arrest helped bring the matter to a quiet end.

- One day, they took me to an interrogation room and played a recording of a woman screaming. It was clear the woman was being harassed and the interrogator said: “Your wife is here and isn’t more than a thousand metres away from you. We’ll do whatever we want to her.” I didn’t know that my wife had actually been released the same night she was arrested, so I was very upset when I heard this threat. I cried and said: “Don’t do anything to my wife!” They brought me a tissue and some water and the interrogator told me to wipe my tears. I said: “I’m not sad for myself. Just don’t do anything to my wife, mother, or sister! What do you want from me?” The interrogator said: “We don’t want anything in particular. Just names.” I said: “You already know how many we are. Most of the others are from NA, like Adel, Davood, and Babak. They were addicts before.”

- During this second round of interrogations, they didn’t physically torture me, but they insulted and threatened me. For example, the interrogator said: “We have an electric chair here, and if you don’t talk, we’ll torture you!” I once heard a man being tortured and, after it was over, they took him to Babak’s cell. His crime had been carrying a weapon. He had been whipped on his bare feet and beaten until he had told them who sold him the weapon. We always knew that the prospect of torture was real.

End of interrogations

- It had been two weeks since our arrest when they took us, one by one, to the interrogation room for the last time. The interrogator explained: “Tonight is the celebration of the three Imams and the night of Islamic compassion, and I want to allow you to call your family.” He continued: “You are only allowed to say ‘hello’, and if you talk about anything else, I’ll hang up.” So I called my mother’s house and asked about my wife, and that was how I learned that she had been released, and I spoke to her. We both missed each other and had been worrying about each other, and we cried. I think our conversation lasted only about one or two minutes.

- After the phone call, the interrogator took me into the yard and said: “We know that your brother is an IRGC member; we know where you worked before. We know that you have been fooled and made a mistake. It’s not your fault!” He read from the Ashura pilgrimage prayer, Nahj al-Balagha sermons and other Islamic texts, and said the Bible had been distorted. He asked if my family knew I had become a Christian, and I told him that none of my family members knew, except my father, who may have found out before he died. He asked for the address of my brother’s workplace. I said: “You know better than me where my brother studies!”

- The interrogator said: “We can detain you in this basement for six months and extend it for another six months, and the extensions will continue. So, you are in our custody as long as we want.”

- Every night, Babak drew lines on the wall to keep track of the number of days we had been detained. After 18 days’ detention, one morning they entered my cell and asked me to lift my clothes to look at my body. They wanted to make sure there were no torture marks remaining on my body. There weren’t any, because it had been a long time since the physical torture. Then they brought me some documents and asked me to sign and fingerprint them. Since I was blindfolded, I told them that I didn’t know what was written. The interrogator replied: “The important thing is that we know what you must sign!” Then he held the documents against the wall, took my hand and told me where to sign. In this way, I was forced to sign and fingerprint documents whose contents I didn’t know.

- Once the interrogator left the room, I looked at the document from under my blindfold. At the top was written: “Names of the Shiraz Apostates”, and next to my name was a number, which was one thousand one hundred and something. It appeared that, before me, they had identified or even arrested over 1,100 Christians in Shiraz!

Prosecutor’s office

- The first time they took us to a court was during the first week of detention, when they brought us before a prosecutor at the Islamic Revolutionary Court of Fars Province. They took us there in a Paykan car, and a driver and agent sat in the front, while the four of us (Adel, Babak, Davood and me) were blindfolded in the back seat. They took us after office hours, when the court was completely closed and led us through the backdoor – that is, via the parking area that was reserved for judges and court staff. All of us were blindfolded all the way to the door of the courtroom, but when we entered, they allowed us to remove our blindfolds.

- We didn’t have a lawyer that day, and they hadn’t told us anything about our right to a lawyer. Inside the courtroom there was a prosecutor named Rezaian, who was also a cleric; the head interrogator, whose pseudonym was “Mr. Shirazi”; and another person whom I recognised from his voice as my interrogator. Each of us had had a different interrogator, and they were all present and all wore green surgical masks. The interrogators were in the room to correct anything we said that they thought incorrect.

- Rezaian handed me a sheet of paper, on which they had written my name, surname, alias, ID number, and charge. They had written our religion as “Zionist Christianity, Protestant branch”, and the charge as: “Acts against internal security, and propaganda activity against the Islamic Republic regime”. When I saw the charge, I was very surprised, because I thought they would charge us with apostasy. I had previously read the final defence of martyr Mehdi Dibaj and prepared to defend myself against that charge.

- Prosecutor Rezaian said: “If you have a statement, write it down.” I wrote that I had been born into a Muslim family and become a Christian. Then I wrote the story of my life and how I became a Christian. He asked in surprise: “What is this that you wrote?” I said: “This is what you call an act against internal security and ‘Zionist’ propaganda activity!”

- Then he told me to write about my trips outside Iran, and I narrated the story of these trips as agreed with my other detained friends. He asked which country we were connected to, and I said that we weren’t connected to any country. Upon hearing this answer, he said in a loud, insulting and contemptuous voice: “You are a group of sheep without a shepherd who are causing chaos in this city! You don’t know what trap you have fallen into! You have entered into a soft war, but you can’t overthrow the government!” I said that we had no intention at all of overthrowing the government. After hearing my statement, he asked me to leave the room. Reading out the charges against us, including the time it took to give our answers, took about 15 to 20 minutes for each of us. The whole process, including driving there and back, took no more than one or two hours. Afterwards, we returned to the detention centre, and the interrogations, or as they called them, “investigations”, continued for weeks.

- At first we thought they were going to release us. But they put us back into the car, blindfolded, and when they told us to take off our blindfolds and get out, we were in front of Adel Abad Prison. Then they took us to the Shiraz Central Detention Centre, which is next to the main prison. One of the officers who took us there was my brother’s close friend.

Central detention centre

- Once we entered the detention centre, which hadn’t long been open, they took our fingerprints. Then we had to hand over our detention warrant to the prison officer. This document declared that we were being placed in “temporary detention”, which is a type of detention that can be extended every three months. This means they can take a prisoner with a “temporary detention” warrant back to the prosecutor’s office and extend the detention so they can continue their interrogations. In addition, during the temporary detention period, at any time the interrogator wants, he can return a prisoner to the IRGC intelligence detention centre to continue interrogations there.

- The prison officer said we weren’t allowed to refer to our charge as “Christianity”, and had to tell the other prisoners our crime was drug trafficking or fraud. But as we passed into the prison and sat and waited for our room to be determined, the prison doctor, Dr Zare, asked us what our charges were while he examined us, and all four of us said that we were there because of our Christian beliefs. Another prisoner who was with us in the reception area said: “Didn’t the prison officer tell you not to say that your crime was Christianity!” We said: “Well, our crime is Christianity. Why shouldn’t we say it?” He replied: “This is Adel Abad. They’ll take you to the basement, to a solitary cell, where they torture people and don’t give you food!” We said: “No matter what they do to us, we’ll still say that we are Christians.”

- The detention centre had four wards, with about 90 people in each. In each ward, they had divided the rooms using three-tiered beds, which acted as the boundaries between rooms, with nine beds in each room.

- They took us to the first ward. The rooms were full of prisoners, and many slept on the floor in the corridors. We were sent to separate rooms, but after talking with the other prisoners, we were eventually all able to be together in one room. Because it was a place for those in temporary detention, prisoners were constantly released – they regularly read out the names of those being released on the loudspeaker – and new prisoners arrived. This was a centre for prisoners who wanted to get their private claimants to drop charges; were waiting for bail to be posted; or looking for a guarantor.

- When we entered the detention centre, it was around 9pm. They hadn’t given us any lunch that day, and it was past dinner time and still we hadn’t been given anything. But that didn’t matter to us. We were happy to be there, as it felt like freedom compared to the conditions in our previous place of detention.

- That night, one of the other prisoners gave us his phone card so that we could call our families. I called my mother’s home and told her that I had been transferred there, and I heard my family clapping and cheering about our new place of detention!

- The temporary detention centre was actually a very large storehouse, which had been divided into five parts. One of the sections was the dining hall, and after eating, it was transformed into a gym so that prisoners could play and exercise. Every four days, it was our ward’s turn to go to the gym and exercise for about 30 minutes to one hour. The gym also had facilities for football and ping-pong. Another section was the prayer room, which was very large so that prisoners from all four wards could pray there. Attendance at the prayer room was mandatory, but those who did not pray or were illiterate usually sat at the far end of the room. This gave us the opportunity to talk to the other people sitting there, and it was here where Babak spoke to one of the prisoners about our Christian faith and he also became a Christian. After a while, the head of the central detention centre called us in and warned us to be careful, using the Persian phrase: “The walls here have mice and mice have ears!”

- We weren’t given any time outdoors to get fresh air. It was August, and the air in the storehouse was extremely hot. They had put fibreglass under the roof as insulation, but there was no cooling system – just an extractor fan. A television was mounted on the wall, and the toilets and bathrooms were at the end of the hall. There were about six or seven toilets, and the same number of bathrooms, but their walls were short, so that only the lower part of your body was covered. And they had installed cameras in every area, including the toilets and bathrooms.

- We hadn’t been allowed to shower during the entire first month of our detention. Only Adel, who suffered with intestinal bleeding and needed to bathe, after getting permission from the interrogators, had been able to wash his head and body from time to time with soap or the washing liquid that was in the bathroom. But the bathroom had only had a cold-water tap, so Adel had had to wash himself with cold water. We asked the prisoners in our new surroundings when the water would be hot, and they said that it would be around 4 or 5 in the morning. So we stayed up until morning to make sure we were the first to take a shower. However, unfortunately, the heaters weren’t on and the water was very cold, as we washed ourselves with soap and shampoo that we had borrowed from other prisoners. We had no towels, either, so we dried ourselves with the prison clothes we had been given, because we had nothing else.

- The prisoners talked to us about the “gift card”, the name given to a particular bank card with which you could buy things from the prison shop. You could buy one for either 20,000 tomans [approx. $20] or 50,000 [$50], and we asked our families to purchase cards for us and send them to us, though it took a few days for them to reach us. One of the prisoners was a young man serving time for being unable to pay his wife’s dowry upon divorce, and he helped with various tasks in the prison. Prisoners like him, who had committed financial “crimes”, were allowed to be more involved in prison affairs. We explained our situation to him and he promised to help us, and when our families sent the cards to us, he quickly delivered them to us.

- Our first purchase with the new cards was a bottle of fizzy drink, which we had been craving. We especially asked for a cold bottle, and drank it with pleasure. As the facilities in that place were very limited, we also used fizzy drinks cans as glasses. We also bought towels, detergent, and biscuits to thank our fellow prisoners for allowing the four of us to be in the same room.

- Meanwhile, Babak and Adel helped a prisoner who was addicted to crystal meth to quit his addiction. They took him to the bathroom every day and massaged him with cold water until the boy was able to completely quit his addiction.

- One day, a prisoner who had a particular animosity towards us, and was spying on prisoners for the prison authorities, loudly declared to everyone that we were Christians. Some time later, a cleric was sent to our room to give us Islamic “guidance”, so to speak. That cleric also invited other prisoners to come to our room to listen to him. At one stage, he said: “I once went to church and saw them wearing hats that looked like funnels on their heads. They had long beards. They served cordials to drink, but of course I didn’t have any because this would have made me impure. They killed sheep…” The prisoner who had been imprisoned for not being able to pay his wife’s dowry, even though he wasn’t a Christian, came to our defence. He was familiar with Christianity and had read the Bible. He said to the cleric: “I read the Bible and these things you are saying show that the church you went to was fake.” His defence was so strong that the mullah became uncomfortable and left the room without answering. But of course, in the following days, he came again to try to “guide” us.

- After about a month in that place, one day they told us to put on our regular clothes, and said: “We are going to transfer you to the main prison in Shiraz.” That was when we realised that we were going to be detained for longer than we had anticipated.

Prison

- When we entered the main prison, they took us to the quarantine section [where prisoners are held before being transferred to different wards or released], which had four rooms with eight prisoners in each. Two prisoners had been placed in charge of keeping order in this section, and they showed us a film about the prison’s regulations. The film explained that we weren’t allowed to wear shorts, sleeveless vests or baggy trousers. It was also forbidden to grow a long beard or moustache.

- One of these prisoners was a journalist, who had been convicted of a billion-dollar fraud, and when we talked, we found out that his brother was a friend of Adel’s. After that, he took Adel to room number one, the same room he was staying in, and shared his food with us and told us to stay with him and to steer clear of the other prisoners.

- The alleged crime of the prisoners in each room was written on the door. Because we were arrested after the 2009 presidential election and our charge was “acting against national security and propagating against the Islamic Republic”, the other prisoners thought we had been arrested for protesting the result of the election. Therefore, when the television broadcasted news related to the election, prisoners would call us and say: “Come here, they have arrested your friends!” And they would ask us which candidate we had supported – Mousavi or Karroubi. We explained the actual reason for our arrest to some prisoners, but we preferred not to explain it to others. However, we did tell most of them that our charges weren’t what they thought.

- Two days after entering the quarantine section of the prison, the head of intelligence for all prisons in Fars Province, named “Mr Tehrani”, came to visit our prison. He was tall and burly, and we were taken to him one by one. Tehrani said: “I read your file. I know everything. Be careful not to talk too much here. If you have anything to say, just say that you want to talk to Tehrani. If you want a book, or anything else, tell me, so that I can give it to you. You have to be careful here. If you make any enemies, then while you are sleeping, or passing them by, you’ll suddenly find they have pushed a sewing needle into your kidney, poured boiling water onto you from the second floor, or cut your face with a razor!” He explained with particular pride that many people had previously been brought to this prison with charges similar to ours. It was clear that Tehrani was trained and professional, and from the way that he spoke, we realised that he was from Tehran. He also had an assistant who took notes regarding everything that was said.

- Tehrani brought us a Quran, some Hafez poems, another Shia prayer book, and a history of Islam book. We had nothing to do, so we read the Hafez book from time to time. Adel was interested in history books, so he also read the history of Islam book and shared with us the parts related to Christianity.

- Every day at 6am we were taken outside to exercise. After exercise, it was breakfast time. In the afternoon, we were allowed to have some “fresh air” time. During that time we could walk, talk to other prisoners, and sometimes play badminton. Every day during this time the four of us prayed together for our house-church groups. We mentioned each of the members by name and asked God to protect them, and for fear not to overcome them.

- Two or three days after entering the quarantine section, I started to notice spots under my armpits and around my groin. However, despite my repeated requests, I wasn’t allowed to go to the hospital. The other prisoners explained to me that these spots were scabies and that I had contracted it due to the dirty and polluted environment. The spots were very itchy, but when I itched them, they would spread to other parts of my body. Finally, they sent me to the infirmary, and I was given some medicine. In addition to taking this medicine, I was advised to avoid itching the spots and to avoid physical contact with other prisoners. I was also told that my clothes should be washed with boiling water, and that since the medicine was dangerous to handle, I should wear gloves when applying it to the spots.

Family visit

- A while after we arrived at the prison, we met a young man named Mr Gholami, who was a prison employee responsible for the quarantine section. He guided us on how to write an application for a family visit. Then, the four of us gave our signed application to the prison authorities, and it was approved that we could receive a visit via a visitor’s booth, within which we could speak to our family member over a phone and see them through a glass screen. The prison visitation schedule was set up such that, one week, men could come for a visit, and the next week, women could come. The visit finally took place and I saw my wife again after two months. Our conversation was very short, but precious, as we were at least able to ask about each other’s well-being.

Wards 10 and 11

- One day, we were taken to the head of the prison, who called us into his room one by one and asked us for what crime we had been detained. I said: “We are Christians.” He asked again: “No, what is your crime?” I replied again: “Well, I am a Christian.” He had asked all of us individually the same thing, and we had all given the same answer. His reaction was mocking: “No, you aren’t allowed to mention that! Otherwise we will make sure that the wall and ceiling come down on your heads!” Then he asked what charge had been written down for us. We said: “Acting against the security of the system.” It seemed that he was aware of the main reason for our arrest, but intended to humiliate and harass us.

- After about a month in quarantine, the four of us were sent to two different wards. Wards 10 and 11 were the wards where prisoners with sentences of more than 10 years or who were facing the death penalty were kept: prisoners who had committed crimes such as murder, rape, smuggling and transporting large quantities of drugs, etc. Davood was sent to ward 10, and Adel, Babak and I were sent to ward 11. One of us was taken to room five, one to room 14, and the other to room 20. We asked to be put in the same room, but the prison authorities refused. However, we could at least see and speak to each other as we went around the ward.

- We had to write our names and alleged crimes on the doors of our rooms. So we wrote that our charges were: “Acting against national security and propaganda activity against the Islamic Republic”. There were nine beds in each room, but about 14 or 15 people. Newly arrived prisoners had to sleep on the floor, which was known as being a “floorsleeper.” My roommates weren’t very alert, because most of them were using drugs, but I introduced myself and they explained the rules of the room to me and said that if I wanted, I could become the “mayor” of the room. They talked to me about the responsibilities of this position, such as food distribution and conflict resolution, but I declined.

- In that ward, several prisoners threatened us with the same actions that Tehrani had described to us. It was clear they had been instructed to threaten us in this way. One of them asked if I recognised him. I looked at him carefully, but didn’t. He told me that he was from such and such a neighbourhood and that he used to go to such and such a mosque. He continued: “Several people have identified you. You have to be very careful not to suddenly find that a sewing needle is stuck into your kidneys, or boiling water poured onto your head. If you even try to report other prisoners, you’ll suddenly see many people attacking you and causing trouble for you.”

- I asked this prisoner if he knew the reason we had been detained. He replied that he had seen my charge on the door of the room, but that he thought there was more to it. Some prisoners who had been in the military or Basij were in prison for crimes such as fraud or sodomy, and they thought I was in prison for those kinds of crimes. Later, a young prisoner who worked in the library informed me that some of the inmates who had been in the prison a long time had managed to get hold of my file and read it, and therefore they had found out what our “crime” was. From that day on, their behaviour towards us actually became softer.

- Wednesdays were bad days because prisoners who were sentenced to death were called to be executed. Sometimes the claimant would pardon them at the last minute, and sometimes the sentence was carried out. Pardons were rarely given, and the prisoners had a tradition that they would make halva and mourn together for the prisoner who had been executed.

- When we were transferred to the main prison, we made a written request for a visit that might take place face-to-face – not behind a glass screen – and it was approved. So one day, my wife, my mother and my sister came to visit me, while Adel, Davood, and Babak were also able to meet their families in this way. The meetings took place in a large hall, which contained a little shop. But our meeting was during Ramadan, so the buffet was closed. We spread out a blanket and sat on it, and were able to be together and talk for about two hours.

Education Ward

- The Education Ward was a ward where prisoners who had particular skills were taken. For example, Adel was a calligrapher and I had skills in design, printing, advertising and computer work, so after a while they transferred us there. During my two or three weeks there, I was in charge of handing out books in the library and digitising the library system.

- There was a small room in this ward, which had been converted into a phone area. It had a phone booth, and we could make calls outside the prison with a card that you could buy from the store. Of course, we often had to queue. Our phone calls usually lasted one or two minutes, and if we needed more time, we had to go early in the morning, when the booth was empty. But because I worked at the library, I had access to the booth at a particular time each day.

- Prison phones are monitored. That’s why even those who had been detained for political or financial reasons didn’t talk about sensitive issues on the phone. This was also the reason why mobile phones and SIM cards were smuggled into the prison. Each room had a mobile phone, and in every room there was an agreement among the prisoners that everyone could use it. In order to do so, you just had to pay a fee, then go to the corner of the room that had been specifically allocated for this purpose, and talk. Or if someone wanted to receive a call, they could give their loved ones the number of that phone.

- My wife hardly left the house after her release, but after a while a friend bought her a new SIM card and phone, and I would call my wife’s new number during the day and ask about her well-being. At night, we would talk about personal and church matters, and because we were using a phone that wasn’t monitored we could talk more easily about church members, our lawyers, and the legal process.

- During the time we were in prison, our families sent a power of attorney form to the prison for us to sign, and that was how they got us a lawyer. But the IRGC contacted him and told him he wasn’t allowed to represent us.

Trial

- One afternoon, we were told to wake up early the next morning because we had to go to court. So, that night we called our families and told them that the next day we would be in court.

- That next day we were given striped blue prison uniforms to wear. Then they handcuffed us – something they only did to people who had committed serious crimes. When we arrived at the prison door, they were even going to put shackles on our feet, but the person in charge of transporting us said there was no need. Then they put us into a car and took us to the court.

- The judge was a cleric named Hojatoleslam Gholamhossein Sobhani-Nia. He was the head of the Islamic Revolutionary Court of Fars Province and of Branch 1 of this Revolutionary Court. He read out our charges and explained that the claimant in our case was the General and Revolutionary Prosecutor of Shiraz, Hojatoleslam Jaber Baneshi. When I was in the IRGC, Baneshi had been an investigator. His title had now changed, and he had become a judge, and later he became a prosecutor. He was also a member of the city’s Security Council.

- There were seven defendants in our case in total, but just six of us were present in the court: Babak, Davood, Adel, Maryam, Mehrdad, and myself. Lawyers representing the four of us still in prison were also there, while Mehrdad came without a lawyer. The seventh person in our case was Heydar, but he wasn’t present in the court. The judge asked where Heydar was, and someone went and whispered something in the judge’s ear. Then the judge said that his absence wasn’t a problem and added: “We’ll make a decision for him in absentia.”

- Sobhani-Nia read out some bits from our file, and asked us to explain ourselves. During our time in prison we had discussed between ourselves all the conversations we’d had with our interrogators, so we felt prepared to answer his questions, and confidently denied any connection to foreign networks. We said we hadn’t engaged in any political activity against the government and added: “Our ID cards show that we participated in elections. We have good employment records and have always been good citizens. We have never even set foot in a police station before now. We encourage people, according to the Bible, to obey the highest authorities of the country; to pay taxes; and to respect the authorities and law enforcement agencies, as it says in Romans 13. We are good citizens.” Those of us who were previously members of NA explained that after becoming Christians, we were freed from addiction; our personalities changed; and we became useful people for our families and communities.

- We denied all the charges brought against us, and our lawyers also requested that instead of the fabricated charge of “acting against the internal security of the country and propagandising against the Islamic Republic”, we be charged with “apostasy”. The judge said: “You are very clever! You want the case to be taken out of my hands and sent to another court, where you’ll be acquitted!”

- The judge cited the interrogators’ report and our signed forced confessions and said: “You confessed! You signed and added your fingerprints to this document!” We explained that we had been forced to write certain things. For example, I had written that our teachers had come from Mexico to a Christian conference abroad. But he told me that I should write that they were also from England and Italy. “The interrogator even forced us to sign and fingerprint a document without reading the contents,” I explained. But Sobhani-Nia didn’t accept this claim. I said that at least he should summon the person whose pseudonym was “Mr Shirazi” and who was in charge of our case, to testify whether he had taken our signatures with our eyes blindfolded or not!

- We were the first people that day to enter the judge’s courtroom, and when we came out it was almost time for the court to close. All the prisoners waiting for their own court sessions were angry because ours had taken so long. Then we were taken back to prison.

- After leaving the court, our families talked to the deputy prosecutor, who was called Mr Mousavitabar, and pleaded with him to release us as soon as possible, but he refused.

Temporary release

- However, a few days later, my friend who worked with me in the prison library told us that he had good news for us and that we were going to be released on bail. Three of us had been issued a bail of 50 million tomans [approx. $50,000], while Mehrdad’s had been set at 100 million tomans [approx. $100,000].

- Our families tried to bail us out, but mine didn’t have the money, so Babak’s mother bailed me out, and on 23 September 2009, about a week to 10 days after the court hearing, we were temporarily released.

- During our time in prison, we tried to serve and love the other prisoners as much as possible, for example by cleaning the room on everyone’s behalf. Many became friends with us. But Babak’s roommates in ward 11 had been better than mine, who were mostly addicts. The day Babak was released, his roommates cried. Even after his release, they called him to ask how he was doing.

Verdict

- About two to three months after our release, we were called and told that the court had issued our sentence, so we went to the court, but Mr Sobhani-Nia’s office had a new administrator. This person gave us a sheet of paper, which he told us to sign, but we said that we couldn’t until we had read our verdict. So he put our entire case file in front of us, and we read it.

- The file contained a report from the IRGC, which had a chart on which it had one header: “The leaders of Tehran, identity known”. Then below this, there was another section containing the names of the Christian leaders of Shiraz, and their responsibilities. They had named me as the head of the church, Babak as the head of internal and external communications; and Mehrdad as the financial manager of the church. Davood, Maryam, Adel, and Heydar had been named as “second in line leaders”, and the judge had determined our punishments based on these titles.

- We all received one-year sentences, but Davood, Maryam, Adel and Heydar’s were suspended, while Mehrdad, Babak and I had to serve ours. For those whose sentences had been suspended, they wouldn’t have to go to prison unless they committed a similar “crime” within a certain period.

- By studying the file, we realised that initially they had sentenced us to two years, and we learned later that our names had reached the authorities in European countries through Christian organisations, and that diplomatic pressure had been exerted on the Islamic Republic to release us more quickly. Due to the foreign pressure exerted on them, they had released us on bail on the day of Eid al-Fitr [marking the end of Ramadan], under the pretext of “Islamic compassion”, and later reduced our sentences.

- We signed the bottom of the verdict, but Babak, Mehrdad, and I appealed within the 20-day legal deadline. Those who had been given suspended sentences didn’t file appeals.

After release

- Unfortunately, after our release, senior Christian leaders abandoned us and cut off contact with us – perhaps because they considered us to no further use, as we had been identified. But my wife and I prayed and, after doing so, we made the decision to continue our Christian activities. So we met with church members, and some were surprised to see us, because it was rumoured that we had recanted our Christian faith in a mosque in Shiraz and had had penitence water poured on our heads. But we assured them that we hadn’t repented at all and that we were committed to our Christian faith. We were very happy to meet our Christian friends again, and hugged each other and cried.

- We formed several new groups, each one consisting of family members who were related to each other. We encouraged them to gather together and to have specific times for prayer and worship. We visited them about two to three times a year, at times when it wouldn’t seem unusual to gather, such as Christmas and Nowruz, etc. When we visited them, we didn’t take our mobile phones with us, travelled on public transport, and tried to get off a few stops before our destination and walk to their homes, to try to make sure we didn’t pose a danger to them.

- After my release, I had trouble making a living. I used to have a shop, but my business license was cancelled by the issuing authority because of my Christian faith and activities. I planned to rent a car and work as a taxi driver, but I needed to get an ID card for that, and when I provided my fingerprints, they found out that I had a criminal record for “acting against internal security and propaganda activities”. At the same time, a friend of mine who lived in our neighbourhood had killed someone in a fight and paid about 50 to 60 million tomans [approx. $50,000-60,000] in “blood money” to the victim’s family, so was released. Now he is a motorcycle courier. This means that he has gone through the identification process and been given a work permit. They considered his crime to be social, but mine to be political, and people who have committed political “offences” aren’t easily allowed to work.

- For a while, I worked as an internal manager and marketer in a takeaway food department, in an NGO called the “Imam Ali” organisation. But the IRGC found out and told the person in charge of the charity about me, and they fired me. I also did some printing and advertising work.

- Then, with a little help from a Christian friend, I managed to get a loan, and with that loan bought a car and started to work as a private driver. But after a while, fuel and gas became expensive and the job was no longer affordable for me.

- The last job I did in Iran was working in a sandwich shop. An old friend managed a shop and needed staff. The owner and his wife were high-ranking officials in the social security organisation of Fars province. My friend hired me because he knew I needed work, but indirectly he asked me to be careful, and said that if anything happened to me, he wouldn’t be able to intervene.

Court of appeal

- The judge of the Court of Appeal, which in most cases acted as a court of confirmation rather than appeal, was responsible for the Intelligence Protection courts of Shiraz province. More than a year after we lodged our appeals, I went to the court’s executive department to follow up on our case. A person named Mr Melli was in charge of that department. He took my national ID card, looked at my file, and said that my sentence had been upheld. I asked him: “What should I do now?” He said that I should sit in the guard’s office until an officer came and took me to prison. I told him that we hadn’t been informed about our verdict, and that I had only come to the court to see what was going on. “Let me at least go and talk to my employer, say goodbye to my family, collect my belongings, and come back when I am prepared to serve the sentence!” I said. He agreed and allowed me to come back another time.

- I returned home and shared the court’s decision with my wife. She was very upset, but I had resolved that I would report myself to the prison and serve my sentence.

- We informed my brother-in-law and my parents-in-law, who wanted my wife to live with them while I was serving my prison sentence, but my wife said that in order to be able to come to the prison for visits, she would prefer to rent a small place in Shiraz and have her grandmother live with her. So we talked to an estate agent, and gave our notice to the landlord of the home we had rented. I also talked to my employer and asked him to find someone else to take on my responsibilities, while he said he would make sure I received my last pay cheque.

Imprisonment or exile

- One day, we had a meeting with Mehrdad, Babak and their families, and talked about preparing for prison. We even brainstormed how we might be able to take our Bibles into prison, perhaps by giving them a new cover under the title of “Stories of the prophets”, or some such. I suggested that we should pray and fast for three days to seek God’s will on whether we should go to prison or leave Iran. We were torn about which choice to make, as both had pros and cons, but it was important to my wife and me that whatever decision we made, we should both be happy about it and agree with it.

- Mehrdad said that he believed God would work through him in prison, so he and Babak decided to serve their sentences. But my wife and I were torn between going and staying.

Leaving Iran

- In the struggle between staying or leaving Iran, I asked my lawyer if we were banned from leaving the country. He assured me that if we had been officially banned, we would have been told. However, he added that it was possible the IRGC or police intelligence department may wish to prevent us from leaving, but that we would only find out once we arrived at an airport or border.

- One Monday in 2011, my wife and I made a firm decision to leave Iran. We had passports, and a relative bought us a ticket to travel by land to Turkey at his own expense, and told us that the family would worry about us until we had crossed the Bazargan border [in north-west Iran]. Well, we left Iran on the Wednesday of that same week, and arrived in Turkey. After that, we went through the asylum process in Turkey for several years. We now live in Ireland, where I help to pastor an Iranian church in Dublin.

*Pseudonym.

0 Comments