By Fred Petrossian

Iran’s hand-picked presidential candidates have used some nice phrases in recent weeks about the rights and “dignity” of the people of Iran in general, and women and minorities in particular, but they have lacked any substance.

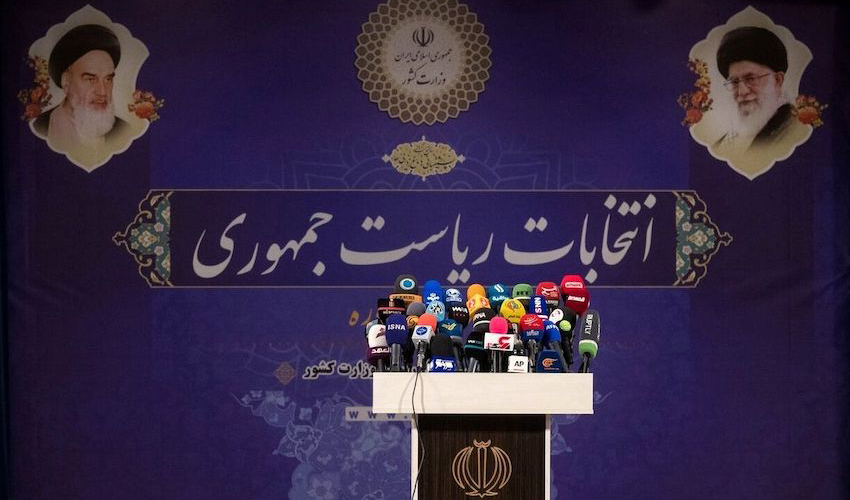

The Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, emphasised the importance of “high participation” in the election, which will conclude tomorrow with a second vote of the remaining two “candidates”, though opponents have labelled the “election” merely a “circus” used by the Islamic Republic to garner legitimacy in the eyes of the world.

Iran’s election cannot be considered to be democratic, given that the unelected Guardian Council decides which candidates to accept and chooses only those perceived as most loyal to the regime.

Meanwhile, the Council itself comprises 12 members – six of whom are appointed directly by the Supreme Leader, while the other six are appointed by the judiciary, which is also selected by the Supreme Leader.

One of the remaining two candidates, Masoud Pezeshkian, 69, a surgeon, former Health Minister and five-term member of parliament, placed the greatest emphasis on religious minorities – especially Sunnis – in his campaign.

“I am deeply affected by the fact that [Sunni] Turkmens, Kurds, Baloch and Talysh peoples are deprived of the proper status and dignity of an Iranian due to religious distinction,” Pezeshkian, who also served as deputy parliamentary speaker, said. “Especially when I remember that these people, who were the creators of our culture and civilisation, are sometimes deprived of their basic rights.”

Like other candidates who have had a prominent presence in the power structures of the Islamic Republic of Iran for decades, Pezeshkian’s words about the status of minorities, women or the economic and political state of affairs were expressed as if he were an opposition figure.

In his statement about ethnic and religious groups, without specifying who was to blame, he spoke of a “they” who “do not know that Iran, without Kurdish culture and identity, will lose its most important component and suffer an irreparable loss; or the zealous and freedom-loving Azeris, who are the revivalists of constitutionalism; or the brave and sincere Baluch and Sistanis; or the faithful and hard-working Armenian and Assyrian compatriots; and the good-thinking and righteous Zoroastrians; and the pure Mandaeans; and the dear Jews; and the great, zealous Arabs, Lur, and Bakhtiari … and the beautiful-minded, patriotic, and pious Turkmens.”

All of which begs the question of who they were who passed discriminatory laws, deprived millions of Iranians of their human and civil rights, and sent thousands of people, including Baha’is, Gonabadi Dervishes, Sunnis, followers of the Yarsan religion, and Christian converts to prison just because of their religious belief and peaceful religious activity.

In truth, “they” were actually the government itself in all its elements, and which all six candidates have been a part of for decades.

Pezeshkian has also stated many times how he is “indebted” and “loyal” to the Supreme Leader, while acknowledging that “Khamenei is the one who determines the general policies” (and therefore has been responsible for suppressing religious and ethnic minorities for decades).

Khamenei himself, to whom Pezeshkian is “indebted”, famously once stated that house-churches were “among the tools of the enemies of the Islamic Republic … to weaken religion in society”.

Meanwhile, one of Pezeshkian’s most high-profile supporters, Mohammad Javad Zarif, the former Foreign Minister, once famously told an American journalist “no-one goes to prison for his beliefs in Iran”, and that stories of Baha’is and others going to prison for their beliefs were “lies”.

Iranians vote with their feet

Despite the calls for “maximum” participation, the first round of the elections last week saw the lowest participation rate since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979.

A second round of votes is set to take place because none of the candidates – in the end only four took part, two having withdrawn – were able to secure a majority.

The government declared the participation rate on 28 June to be 39.1% – though outside observers suggested the real figure was much lower – while 4% per cent of votes (about one million) were discovered to be invalid.

Mostafa Pourmohammadi, 64, one of the senior officials of the Ministry of Intelligence at the time of the “chain murders” of dissidents, whose victims included Christian leaders such as Haik Hovsepian, Mehdi Dibaj, and Tateos Michaelian, secured only around 200,000 votes – or, in other words, five times fewer than the number of spoiled ballots.

Pezeshkian, and Saeed Jalili, 58, former chief nuclear negotiator and university lecturer, made it to the next round, while parliamentary speaker Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf was eliminated.

This latest loud “no” of Iranian citizens has undoubtedly once again challenged the legitimacy of the Islamic Republic, as has even been admitted by one of the surviving “candidates”.

“It is not acceptable that 60% of the population does not come to the polls, and this is worrying,” Pezeshkian said.

“When we don’t give Sunnis, Kurds, and Arabs a place in employment and high positions, this trend will lead to a decrease in participation,” he added, also name-checking women and minorities and saying it was a “natural” consequence for any group whose rights were ignored.

Jalili said that he agreed, but that such subjects shouldn’t be discussed only during an election. However, neither Jalili nor Pezeshkian gave any explanation for why the rights of minorities and women have been violated over the past 45 years, nor how they might change the laws of the Islamic Republic.

And so the second round of “elections” is set to take place, with some warning that Jalili believes in a “permanent war” and dividing the world into “evil and good”, and others fearing his “election” could lead to a further worsening of the sanctions placed on Iran during his time in office.

But many Iranians see little difference between Jalili, who has been labelled a “conservative fundamentalist”, and Pezeshkian, who has been called a “fundamentalist reformer”.

All six candidates have been in positions in which they have directly and indirectly played a role in suppressing protests and legitimising government repression, including Jalili as member of the Supreme National Security Council, and Pezeshkian, who boasted about his role in imposing hijab in universities and hospitals, as well as closing the women’s section of a medical school because it was “not in line” with his beliefs.

So whatever words may have been spoken, until all Iranians – regardless of gender, ethnicity, religion, etc. – are afforded basic human rights, slogans such as “Iran for all Iranians” or even words like “Iranian nation and people”, “women”, “minorities”, and “ethnicities” are only the latest propaganda tools, which after 45 years of the Islamic Republic neither the narrator nor the audience believes in any more.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks