Photo: Christian Blind Mission

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the founding by a German Protestant pastor of Iran’s first school for the blind.

Ernst Jakob Christoffel, who became known in Iran as the “German father of the blind”, made the Braille alphabet accessible to Persians and Armenians, and founded schools in the cities of Tabriz, in the northwest, and Isfahan, the former capital.

Born in 1876 to a Christian family in Germany, whose “home was open to the needy”, Christoffel studied theology in Switzerland, before moving to Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) in 1904 with his sister, Hedwig, to manage two orphanages set up for Armenian children whose parents had been killed by the Ottomans.

Four years later, the siblings independently raised funds to establish a shelter for the blind and disabled named “Bethesda”, from the Aramaic word for “kindness”, or “steadfast love”.

Due to Islamic laws, they could not engage in Christian evangelism, but Christoffel preached that “to love is a sermon that everyone understands”.

It was during his time in Asia Minor that Christoffel invented the Braille alphabet for Armenians, while he also wrote several textbooks for his students, in various fields.

The pastor was forced to leave the Ottoman Empire in 1915, at the time of the Armenian genocide, but returned in 1919. However, he was not permitted to reopen his school, and five years later moved to Iran, perceiving the country to be more tolerant.

Christoffel started the first school for the blind in the history of Iran in 1925 in Tabriz, and a few years later moved to Isfahan, where he established a second school, which not only taught the blind to read and write, but also empowered them to learn skills including farming and carpentry.

Christoffel’s Isfahan school, which was open to both boys and girls, was led by German missionaries but also enabled students and graduates to take on various responsibilities.

The school in Isfahan (Photo: CBM)

Famous figures from the school’s past

One of the Isfahan school’s most famous graduates, the musician, poet and journalist Eskandar Abadi, told Article18 about his time there:

“Mr Christoffel not only supervised, but also taught. He prepared the graduates of the school to take on supervisory and management roles. One of these people was a respectable person named Asadollah Partovi Nejad, who was from Azari origin, knew Armenian, Turkish, Persian, and German. Another was Asatour Matossian, of Armenian origin, who was the superintendent of the school and in charge of the library, and was fluent in German.”

Like many of Christoffel’s students, Abadi was not from a Christian family; students came from all religions and denominations.

“We went to regular schools, and people in the institution would write these textbooks in Braille,” Abadi added. “Christoffel translated the books into Persian Braille, and the first book in Braille was the Gospel of John.”

The former Anglican bishop of Iran, Hassan Dehqani-Tafti, who was forced to flee Iran following the 1979 revolution, taught at the school in his teenage years, and wrote about his experiences there and about Christoffel in his book, ‘The Hard Awakening’:

“I remember as a schoolboy of fifteen going to teach there. Then the Second World War broke out, and in 1941, after Allied armies had occupied Iran, Christoffel was interned and deported by the British, leaving his mission orphaned overnight. It thus became the responsibility of the diocese.”

The bishop added: “After the war, Pastor Christoffel, now an old man, returned to the country” and took up his old responsibilities again.

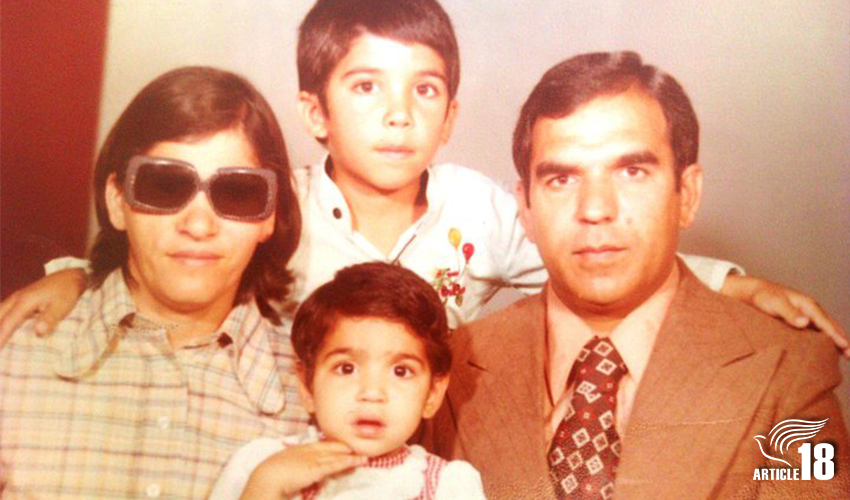

Meanwhile, Rev Hossein Soodmand, who was later executed for apostasy, served for a time as the chaplain of the Nur Ayin Institute for girls in Isfahan, another blind school set up by the Church, where he met his wife, Mahtab.

Rev Hossein Soodmand met his wife Mahtab at the Nur Ayin Institute for the Blind in Isfahan, where he served as chaplain.

An enduring legacy

Christoffel passed away in Isfahan at the age of 79 in 1955, and was buried in the Armenian cemetery in Isfahan. Yet the activities that this Protestant pastor established for the blind continued both in Iran and around the world.

Last year alone, the Christian Blind Mission (CBM), which the pastor founded and was once known as the Christoffel Blind Mission, was involved in 370 projects in 40 countries. The charity also works to promote the rights of the disabled among politicians and governments around the world, and in 2023 supported more than 62 million people in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The organisation assists the deaf and those with other disabilities, with the stated aim of “break[ing] the cycle of poverty and disability in developing countries and creat[ing] a better quality of life and equal opportunities for people with disabilities”.

This is the same message and activity that Christoffel pursued, which can be summarised in one sentence: “To love is the sermon that everyone understands.”

The inscription on Christoffel’s grave reads: “Here lies in the peace of God, after more than 50 years of missionary work, Pastor Ernst Jakob Christoffel, the father of Blind people and persons with disabilities.” (Photo: CBM)

Confiscation and looting after the revolution

Before the 1979 revolution, Christian activities related to the blind in Isfahan included the Christoffel Organisation for Blind (for boys), the Nur Ayin Institute for girls, and the Cyrus the Great farm for agricultural training.

However, after the revolution several institutions belonging to the Church were subjected to invasion, confiscation and looting by Islamists, including the blind school, as well as the hospitals of Shiraz and Isfahan, and buildings and gardens of the Assemblies of God Church.

The Christian hospital is Isfahan is still operational, though it has been officially renamed the “Jesus Son of Mary Hospital”.

“After the revolution, the Islamists stormed the school and took possession of it,” Abadi explained. “I, along with a group, protested this act and went to the Revolutionary Committee about the situation that had arisen. They told us that they would investigate. The result of the investigation was that they issued an arrest warrant for me.”

Several articles have been published in Persian-language media in recent years about the looting of blind institutions after the revolution and how these deprived this segment of society of the services that were available to them before the revolution.

Ramezan Zhiani, a member of the Association of the Blind in Iran, told one Iranian news site in 2020 about the farm near Isfahan, where before the revolution the blind were giving agricultural and animal husbandry training.

“The blind would go to the villages after learning, and do agricultural and animal husbandry work,” Zhiani said.

However, this farm, like many other Christian institutions, was confiscated after the revolution and placed under the control of the State Welfare Organisation, which Zhiani said then “sold a number of machinery, tractors, cows and sheep”.

Houshang Mazaheri, a writer and researcher living in Isfahan, told the same news site: “The original owners of these buildings were Persian-speaking Christians, and they endowed them to the blind.”

He added: “This building and other properties were confiscated in 1979. Now they are under the control of the Welfare Organisation, the governorate, and the Mostazafan Foundation [an organisation under the control of the Supreme Leader].”

Article18’s director, Mansour Borji, explained in 2022, after Bishop Dehqani-Tafti’s former residence, another property confiscated following the revolution, was turned into a museum, that the Mostazafan Foundation was “set up at the beginning of the revolution and used to seize properties belonging to political opponents and affiliates of the former regime, as well as religious minorities such as Christians, Jews and Baha’is, who were some of the first victims of the revolutionary fervour that swept across the country”.

The former residence of the Anglican Bishop of Iran is now a museum (Photo: Twitter @Alireza_E_1999)

Many of the properties and land confiscated from Christian organisations after 1979 had a high financial value, totalling approximately 80 million dollars, according to another 2020 article by Persian-language media.

“These buildings are in the best parts of Isfahan,” Mazaheri explained. “The institutions related to the blind community in Isfahan are in a deplorable condition today, and some of them are no longer under the control of any blind person and have been repurposed.”

When they protested, Zhiani said the authorities responded that the buildings were now “in the possession of the government, and they can change them as they wish”.

“When we said they were endowed for the affairs of the blind, they said they were non-Muslims and their property was confiscated,” he said.

Zhiani said that even the fatwas of Shia leaders – including the Supreme Leader, who proclaimed that money given for a particular purpose, such as for a religious group, “must be spent in the same direction” – were ignored.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks