By Fred Petrossian

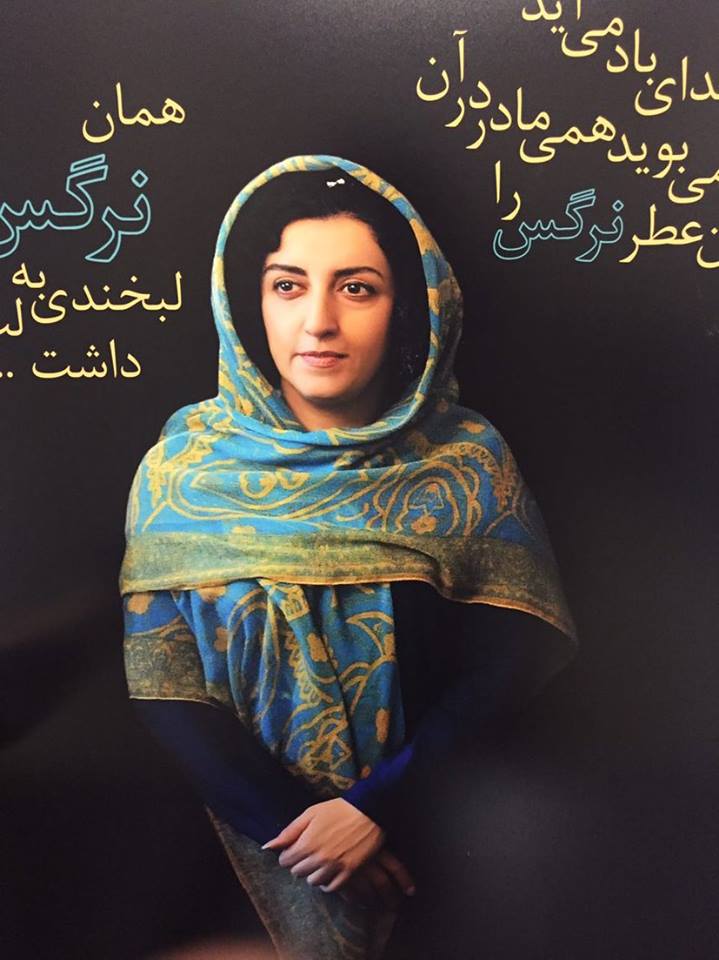

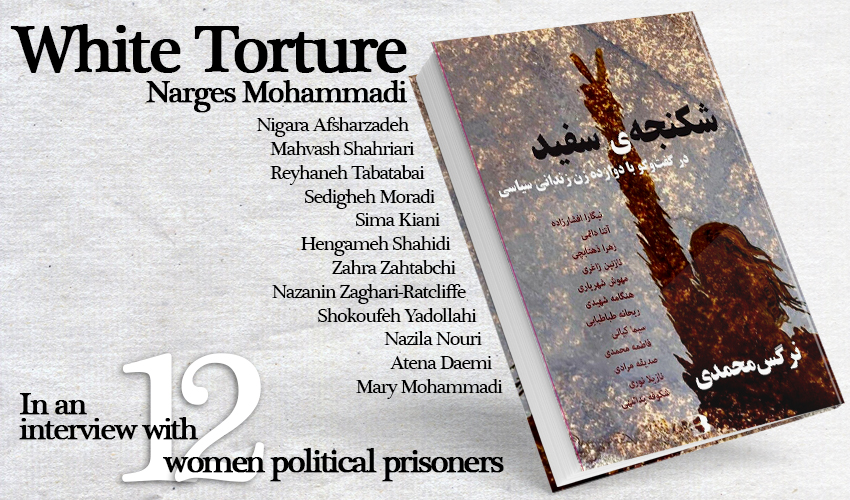

Christian convert Mary Mohammadi is among 12 female current and former prisoners of conscience interviewed as part of a new book on “white torture” inside Iran’s prisons.

The book, written by Narges Mohammadi, who was yesterday released after over five years in prison, also includes the testimonies of two Baha’is and two Sufi dervishes – other oppressed religious minorities in Iran – and British-Iranian national Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe.

The 12 interviewees highlight the numerous ways in which “white torture” was used against them, including solitary confinement, prolonged interrogations, threats to family members, and lack of access to medical care.

The author warns that the effects of these tortures will be lifelong.

Christian convert Mary Mohammadi, who served six months in prison for her membership of a house-church and was given another suspended sentence earlier this year for her part in Tehran protests, explained the “terrible” insults she was subjected to, particularly targeting her parents and her Christian faith.

“For example, they would call the church a gambling house, or say, ‘Why do you read the Bible? Go read the Qur’an!’” Mary explained.

“They would go into the most private corners of my life, which had nothing to do with them at all, and make derogatory remarks. And I couldn’t understand why, when I was interrogated about Christianity, I was blindfolded and made to face the wall – and they would only take it off when I was writing – but then when they wanted to talk to me about personal issues as a woman, I was not blindfolded and made to look at them.”

Mary said that some questions they asked her were “very personal, and no-one has the right to question you about them”, and that “after long, heavy interrogations, I cried, I called on Christ, I spoke to Him, and I prayed”.

‘I’d rather be interrogated than left alone in my cell’

One of the most striking elements of the book is the interviewees’ depictions of the immense loneliness they experienced in solitary confinement.

Nigara Afsharzadeh, a Turkmen national given a five-year sentence in 2014 for alleged spying, explains how she was reduced to talking to ants.

“The cell was silent and there was no sound,” she said. “I scoured the cell just to find something like an ant, and whenever I did, I would talk to it for hours.

“When they brought me lunch, I would crush up some rice and throw it on the floor to attract an ant. I just wanted another living thing in my cell! I was overjoyed when a fly came in one time!”

Sedigheh Moradi, who has spent several periods in prison for her alleged links to dissident groups, explained how on one occasion she was so happy to be joined in her cell by another prisoner, a Christian woman, that “when she came into the cell and took off her blindfold, I hugged and kissed her”.

Baha’i former prisoner of conscience Sima Kiani summed up the sentiment of so many others when she said: “I would rather be interrogated than left alone in a cell.”

Rights activist Atena Daemi, who is currently serving a new two-year sentence after already spending five years in prison, explained solitary confinement as “like a closed box” or “a tin which you feel is being pounded outside by a hammer, to crush it”.

“All the time, suddenly and without warning, they will open the door with a loud crash,” she said. “They have the power to do whatever they want with you, and you have no power at all.”

Threats and deprivations

Another pattern in the book is the huge range of different tactics employed by interrogators in an effort to bend the prisoner to their will.

The former prisoners explain that during interrogations it became clear that the interrogators weren’t looking so much for information – they said it seemed they already knew everything – but that instead they sought only to demoralise the prisoner so much that they would confess to their alleged crimes and do anything else they wanted.

Among the tactics employed are frequent threats to family members.

Mahvash Shahriari, another Baha’i citizen who spent 10 years in prison, said the threats made against her husband and son were “the most difficult” aspects of her interrogations.

“The interrogator told me that your son comes here twice a week, and this is ‘dangerous’ because there he may have an ‘accident’, or that your husband shouldn’t come because, if he does, he will be arrested and executed immediately for apostasy,” she said.

Zahra Zahtabchi, who is serving a 10-year sentence for alleged links with the MKO opposition group, said that when she told her interrogators that her daughters may attend her trial, she was told: “Your sentence is death, so it would be better if they didn’t come.”

Meanwhile, Hengameh Shahidi, a journalist and rights activist sentenced in 2018 to 12 years and nine months in prison, explained how one interrogator told her that he loved her, and even waited for her after her release from prison so that he could propose to her.

“He promised that if I married him, he would close my case forever,” she said. “My answer was that I was willing to accept any sentence imposed on me provided I never had to see him again.”

Some of the tactics were more subtle. Reyhaneh Tabatabaei, another journalist and activist tried three times on charges of “propaganda against the state”, explained that she had been given a war novel to read in prison, which she read seven times, and “later realised how reading this book and imagining scenes of war and killing and death, while in a cell, put more pressure on me”.

But others were very obvious. Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who is on temporary released from prison but still faces the threat of fresh charges, explained how she was denied medical care in prison, including even tablets prescribed for her, and that when prison guards came to bring her food, they would constantly sniff their noses, which put her off her food.

Sufi dervish Nazila Nouri, who spent a year in prison, said the toilet in her cell had no door, nor wall to provide you with any semblance of privacy.

“The sewage was leaking out, and the cell stunk so much that it made us nauseous,” she said.

Resistance and hope

Yet despite all they have endured, there is a real message of hope in the book, evidence that any attempts to crush their spirits have failed.

“I know that the future of my country will be bright, and that prejudice, hatred and enmity will soon disappear,” Sima Kiani says.

Hengameh Shahidi, who has undergone several hunger strikes during her incarceration, said such strikes have provided her and prisoners like her with a way of “showing resistance and protesting against oppression”.

So while ‘White Torture’ is a book about pain, it is also a portrayal of hope and resistance.

‘White Torture’ was published in Persian at the end of August. Translations into English, Swedish and German are expected to be finalised later this month.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks