by Steve Dew-Jones | 5 May 2023 | News

Researchers found that many victims’ devices were first infected near police stations or border posts. (Photo: Lookout) Intelligence officers belonging to the Law Enforcement Command of the Islamic Republic of Iran, or FARAJA, are using spyware to monitor...

by Steve Dew-Jones | 2 May 2023 | News

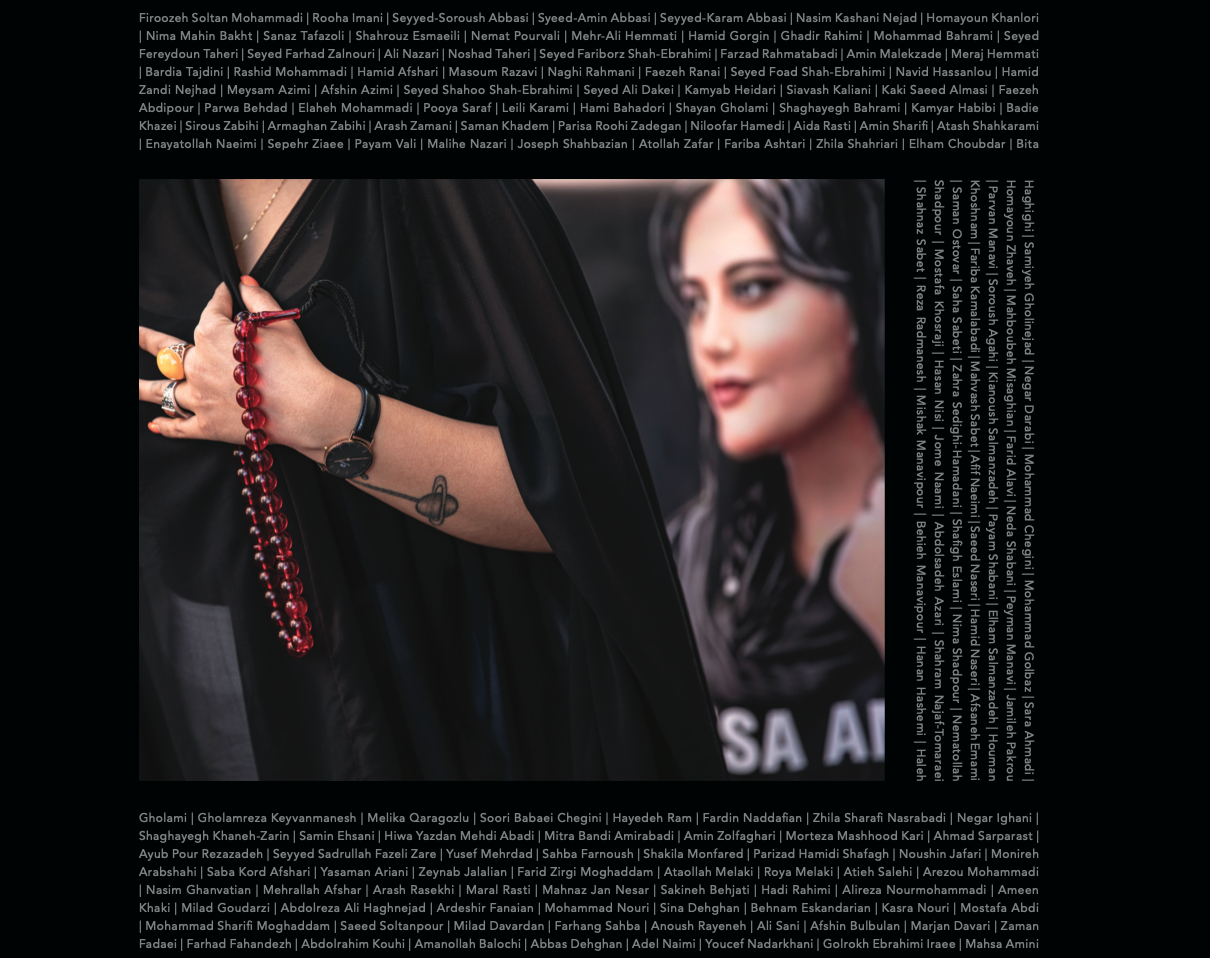

The “sharply deteriorated religious-freedom conditions” in Iran are the focus of the cover and introduction to the latest annual report by the US Commission on International Religious Freedom. The cover of the report, which was published yesterday, features a...

by Steve Dew-Jones | 2 May 2023 | Reports

The “sharply deteriorated religious-freedom conditions” in Iran are the focus of the cover and introduction to the latest annual report by the US Commission on International Religious Freedom. The cover of the report, which was published yesterday, features a...

by Steve Dew-Jones | 26 Apr 2023 | News

A 50-year-old Christian convert whose son has been battling leukaemia for five years was released from prison on Monday, two days before his 25th birthday. Malihe Nazari, who was serving a six-year prison sentence in Tehran’s Evin Prison for “acting against national...

by Steve Dew-Jones | 22 Apr 2023 | Notes from Prison

This is the twelfth and last of a series of articles by Mojtaba Hosseini, an Iranian convert to Christianity who spent more than three years in prison in the southern city of Shiraz because of his membership of a house-church. Mojtaba’s first note from prison...