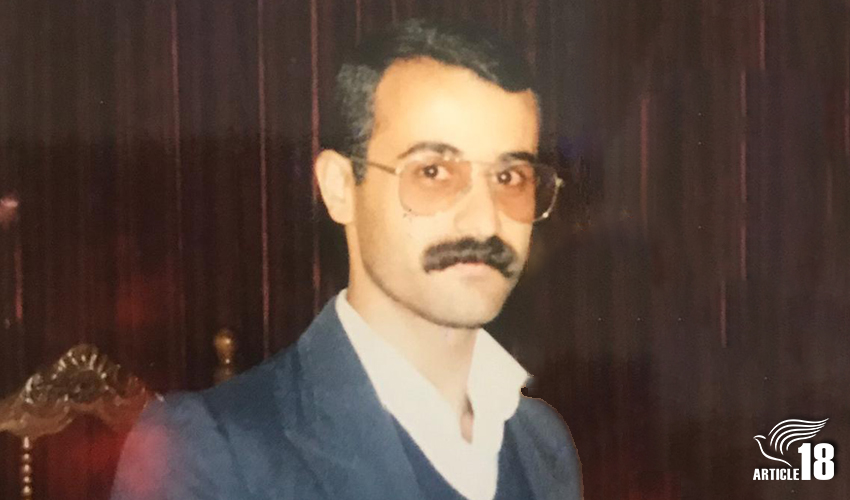

At 6am on 28 September 1996, Christian convert Mohammad Bagher Yusefi (known as “Ravanbakhsh”, or “soul giver”) left his home in Sari, northern Iran, at his wife Akhtar’s request, to buy some bread.

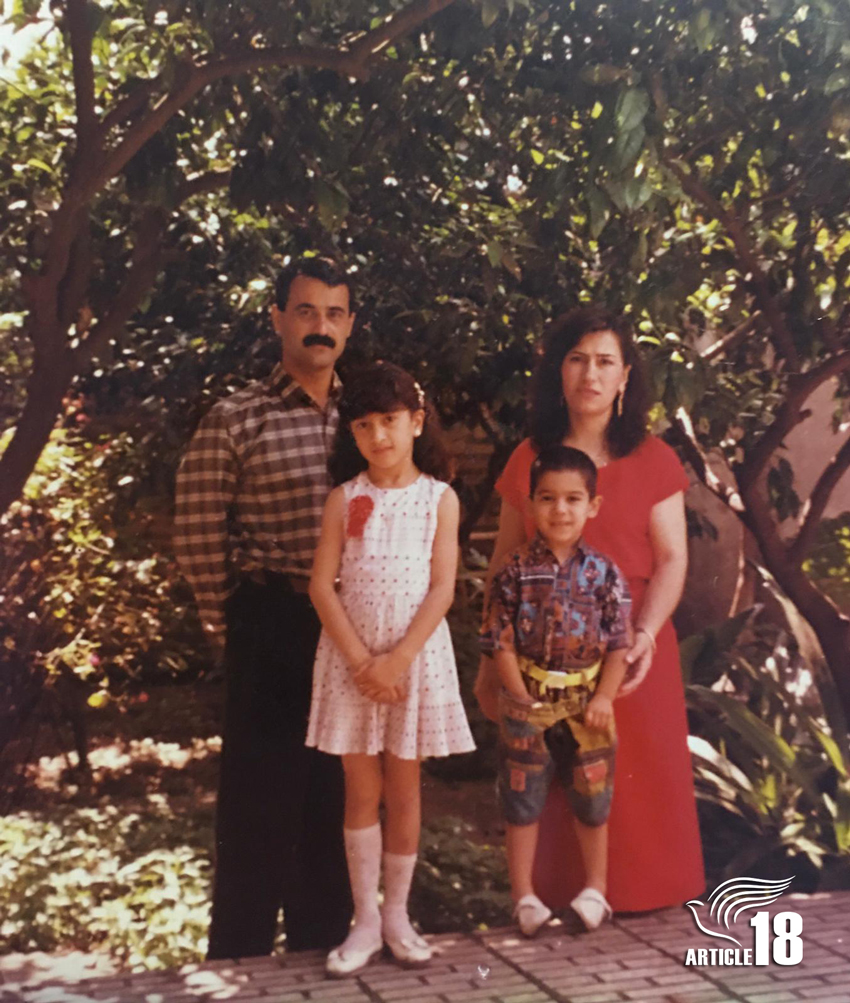

He’d agreed to return home soon afterwards to take the children – Ramsina (10), and Stephen (7) – to school, as he often did.

But on this occasion, the 32-year-old never returned home.

Instead, an hour after leaving, he called his wife and said just one short sentence: “Take care of yourself and the children.”

And then the phone cut off.

The next time Akhtar received a call, it was from the local authorities, at around 4pm the same day, telling her that her husband had had an “accident”.

“I said to myself that his car is still at home,” Akhtar recalled in a conversation with Article18. “So how could he have been in an accident?”

When she arrived at the courthouse, Akhtar was told that her husband had committed suicide – his body had been found hanging from a tree a long way from their home – and was presented with a note that read: “I have a family problem and am unhappy with life and want to commit suicide.”

“They didn’t even give us the note,” Akhtar said. “The only held it up for a moment.”

Akhtar says she knew it was “impossible” that her husband had committed suicide, but in the days that followed both she and her mother-in-law, who she says “loved me very much”, were put under intense pressure to give their signatures to pre-written statements acknowledging that Ravanbakhsh had taken his own life.

And, under pressure, they did.

“My mother-in-law was worried that I might be accused of apostasy,” Akhtar recalls.

Akhtar adds that she was further pressured to say that she and Ravanbakhsh had had an argument and that he had left in a rage and committed suicide.

“I said that I wouldn’t accept such a thing even if you took my life!” she said.

When Akhtar refused to do this, her husband’s family was told they should sue her.

“Every effort was made to make us accept it was a suicide,” Akhtar explained.

But there were few who really believed it, and Amnesty International later included Ravanbakhsh’s death in its 1997 report on “unlawful state killings” by the Iranian regime.

A pattern

Ravanbakhsh wasn’t the first Iranian Christian to die in suspicious circumstances after the 1979 revolution.

Just eight days after the birth of the Islamic Republic, Rev Arastoo Sayyah was murdered in his church office in Shiraz.

A year later, Bahram Dehqani-Tafti, the only son of the first ethnic Persian Anglican bishop, was driven to a remote area near Tehran’s Evin Prison and shot dead. His father had previously survived an assassination attempt, and his secretary was later also shot.

In 1990, Hossein Soodmand, who Akhtar describes as “like a father” to her, was hanged for apostasy and remains the only Iranian Christian officially killed on such a charge.

Then, in the space of six months in 1994, first Iranian-Armenian pastor Haik Hovsepian and then Rev Mehdi Dibaj and Rev Tateos Michaelian were found dead following their own “accidents”.

Both Rev Hovsepian and Rev Dibaj had been very significant figures in Ravanbakhsh and Akhtar’s lives.

Ravanbakhsh was ordained by Rev Hovsepian and later pastored his old church in Gorgan. The couple had even moved into his old house at first, before being ordered not to live there.

Meanwhile, when Rev Dibaj was in prison, it had been Ravanbakhsh and Akhtar that had looked after his two sons – they lived with them for six years – and it was to their house that he would come when given any leave from prison.

So, needless to say, when Akhtar was told her husband had committed suicide, she had good reason to believe there may be another explanation.

Remembering Ravanbakhsh

Akhtar describes her husband as “a very good and faithful man” and keen evangelist – the reason for his nickname.

“I married him because of his faith,” she said.

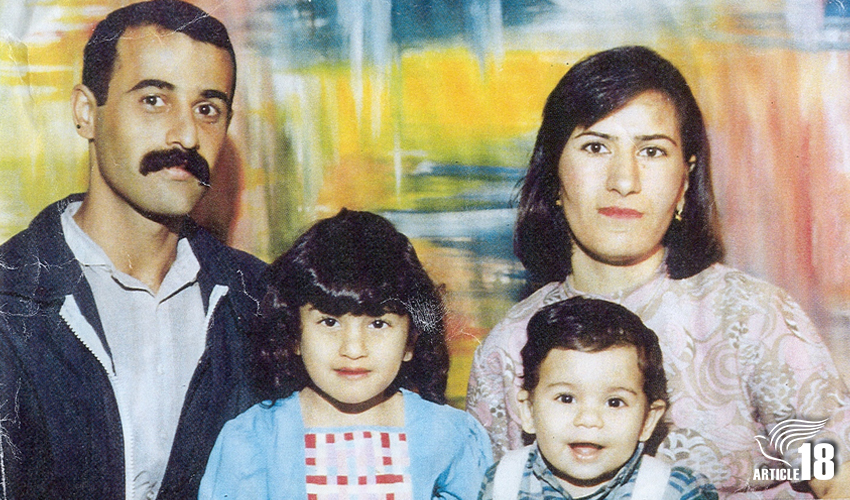

The couple had gotten to know each other at the Garden of Sharon in Karaj, a Christian retreat centre later confiscated by the Executive Headquarters of Iman’s Directive (EIKO), an organisation under the direct stewardship of Iran’s Supreme Leader.

Akhtar describes Ravanbakhsh, who became a Christian at the age of 24 after accidentally coming across a Christian radio broadcast, as a simple man with simple tastes, and recalls how he had to hire a suit, trousers and shoes for their wedding.

“Our wedding ceremony was very simple,” she added.

She also says he was “very obedient” in his role as a church leader, serving Gorgan, Sari and the surrounding area.

“My husband was a very good man, and very obedient to the church and its pastors,” Akhtar said.

The day before his death, Ravanbakhsh and Akhtar had been with some church members on a day trip, but she recalls her husband seeming “very worried”.

“He didn’t say anything when I asked, but I felt that he had been summoned again for questioning,” Akhtar recalled. “When we came back home, before going to sleep he said that he had to go out early in the morning to pray and meet someone.”

Ravanbakhsh had been taken for interrogation several times before, including just a week after the two converts had married, so when he went missing, Akhtar naturally “thought he must have been taken in for questioning again”.

But this time, the reality was even harder to compute.

Life after Ravanbakhsh

Akhtar was prevented from leaving Iran for four years after her husband’s death – an exit ban was placed against her name.

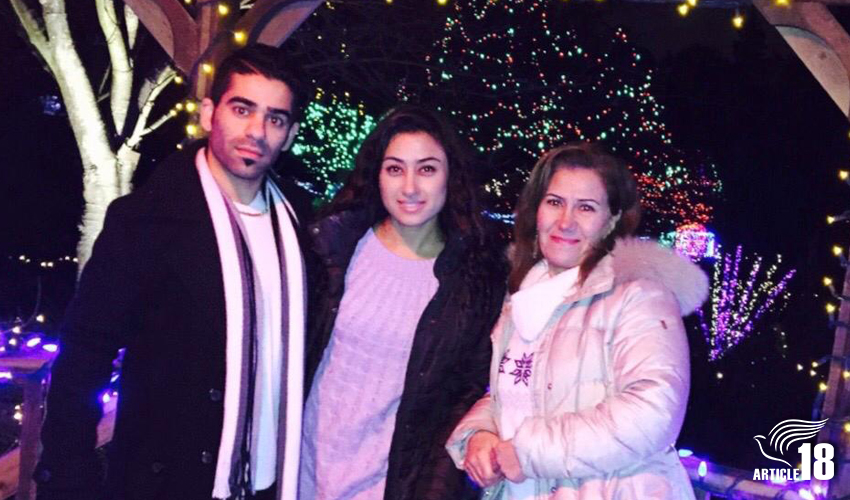

But in 2000, she and the children managed to leave the country for South Korea, where they lived in a village near Seoul for three years, ministering to Iranian Christians there.

Then in 2003, the family relocated to Canada, where they still reside.

For seven years, Akhtar went on annual trips to Afghanistan with a Christian organisation that valued her Persian tongue.

But she explained that her ministry to this organisation came to an abrupt halt in 2014 when the leader of the group, a South African, and his two children were killed by the Taliban.

“After the assassination, I still wanted to go to Afghanistan,” Akhtar explained, recalling this latest tragedy to cross her path. “But my children were alone in Canada, and I was worried that if something happened to me, they would be left homeless.”

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks