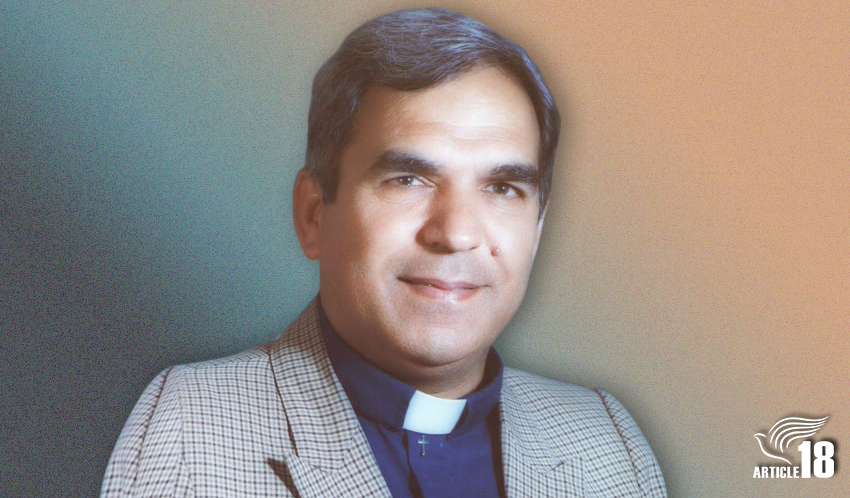

Today is the 30th anniversary of the hanging of Iranian Christian convert Rev Hossein Soodmand for “apostasy”.

Hossein had been arrested a few weeks beforehand, and was executed following a ruling by an Islamic clerical court, without his family’s knowledge.

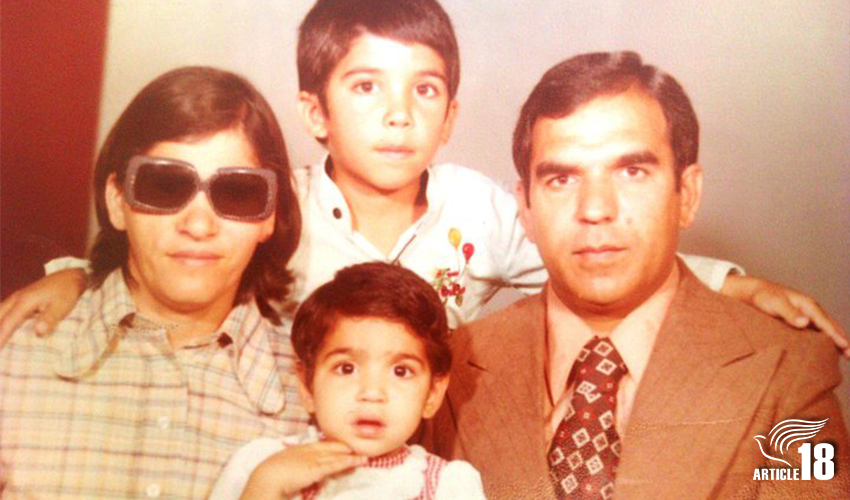

His wife, Mahtab, who is blind, and four children – Ramtin (15), Rashin (12), and twins Arya and Arian (nine) – only found out about his death after other senior church leaders were summoned to the court.

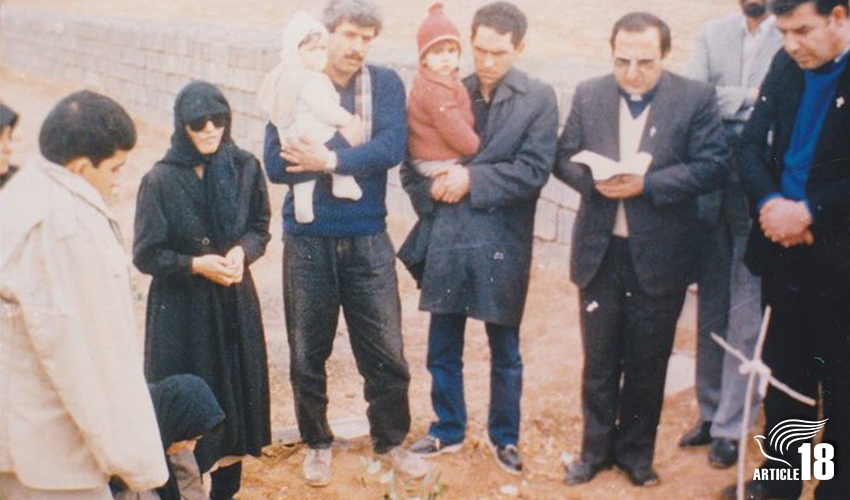

They were told Hossein had been executed and his body buried in an unmarked grave outside the walls of a Mashhad cemetery – an area reserved for the “accursed”.

So Hossein’s family were not afforded any opportunity to bid him farewell, nor even to hear his final wishes. And, despite their pleas, they have never been permitted even to erect a simple headstone above his resting place.

To add insult to injury, during a visit to the grave last year, Hossein’s family discovered that even the basic concrete slab that marked his place of burial had been demolished.

All that now remains is the soil under which he was once laid.

Who was Hossein Soodmand?

Hossein was born in 1940 to a Muslim family in the conservative Shia city of Mashhad in north-eastern Iran.

He converted to Christianity during his military service in Ahvaz, after becoming friends with an Iranian-Armenian Christian.

When he returned home and told his family about his decision, Hossein was told to leave.

So he moved to Tehran, where he worked as a street seller and in time came to know the Rev Mehdi Dibaj, a fellow convert to Christianity who would also later pay with his life for his own act of “apostasy”.

Hossein then moved to Isfahan, where he worked at the Anglican-run institute for the blind, and it was here that he met his wife, Mahtab.

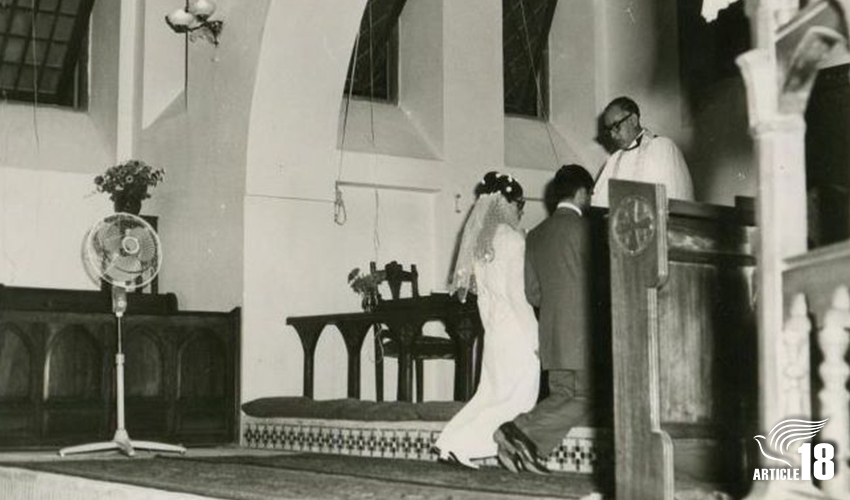

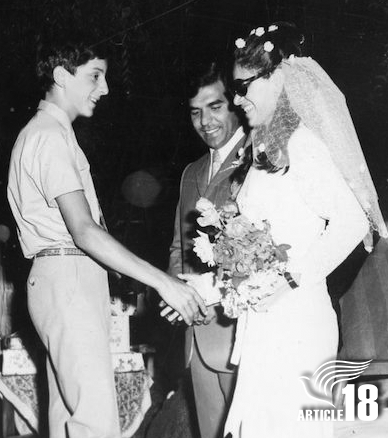

They married in 1970, in a service conducted by another Christian convert, Rev Arastoo Sayyah, who was also later killed because of his choice to leave Islam.

In 1977, Hossein became the assistant pastor of the Assemblies of God church in Isfahan, which was under the stewardship of Edward Hovsepian-Mehr – now superintendent of the Council of United Iranian Churches (Hamgaam) in Europe.

When Edward was posted to another city, Hossein took over the leadership of the church and was ordained by Edward’s brother, Haik – superintendent of the Assemblies of God churches in Iran, and another Iranian Christian to later pay the ultimate price for his faith.

In 1980, after the confiscation of the Christian-run hospital and institution for the blind in Isfahan, Hossein moved back to Mashhad with the aim of planting a church in his home city.

But though the church thrived, the local authorities – in what is one of Iran’s most religious cities and a place of pilgrimage for millions of Shia Muslims every year – refused Hossein permission to build a church.

Instead, he was initially permitted to host the church in his home, above which he erected a sign, declaring it the Assemblies of God Church of Mashhad.

But Hossein, who was a keen evangelist and distributed Bibles across Iran, continued to be viewed with suspicion and, following the death of Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989, he was told his church must close.

Hossein continued to meet with his congregation in secret, but he was regularly arrested and detained, then usually released after a few days.

However, in October 1990, Hossein was held for longer than usual, spending one month in solitary confinement before being released after complaints from Bishop Haik.

But Hossein was re-arrested just a few weeks later, and this time he never returned home.

According to the report of the UN’s special rapporteur at the time, Reynaldo Galindo Pohl, Hossein had been charged with “apostasy, propagating Christianity, distributing Christian literature, and setting up an illegal church”.

Hossein remains the only Iranian Christian to have been officially executed for his “apostasy”, though others have been sentenced to death – only to see the ruling overturned after an outcry – while some of Hossein’s closest friends, including Arastoo, Haik and Mehdi, are among the seven Christians to have been killed extrajudicially since the revolution.

A son’s reflections

On the 30th anniversary of his father’s death, Hossein’s eldest child, Ramtin, shared these reflections on Facebook:

“The day before – that means on Sunday – we were informed by Tehran that the council of [Assemblies of God] pastors, according to the request of one of the departments of the special clerical court of the city of Mashhad, was on its way to our city.

“So this council, composed of the bishop of the Assemblies of God churches [Haik Hovsepian], and some other pastors, arrived in Mashhad on the first available flight and immediately went to where they were summoned.

“The twins went to school in the morning, but Rashin and I were at home. Maybe Rashin thought Dad would return that day and that he should find tea prepared for him when he arrived, as he liked.

“Mum was sitting in the living room with two ladies – Akhtar [Ravanbakhsh’s wife] and Tahmineh [a church member]. Nobody spoke. They didn’t even dare to make predictions about what may be happening. We were all waiting for the return of the members of the council.

“With the sound of the doorbell, we all jumped from our seats and somebody pressed the intercom button. I went quickly to the window in my father’s room and from there I looked down into the courtyard.

“None of the men who stood in the courtyard below raised their heads. To this day, each of them is revered in my eyes, and will remain so, but what was going on in their hearts on that day that they didn’t even respond to my muted greeting?

“I understood everything in that moment – that they were the messengers of bitter news.

“It took them a few minutes to make it up the few steps. Pastor Leon [Hairapetian] came in first, followed by Ravanbakhsh – both upset and worried.

“The next to arrive was dear Haik. He did not smile, nor was he worried. He remained resolute. Extremely resolute.

“That strengthened my heart a little, but…

“Thirty years have passed since that bitter day.

“Still, my heart remains strong.”

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks