by Steve Dew-Jones | 10 Aug 2023 | News

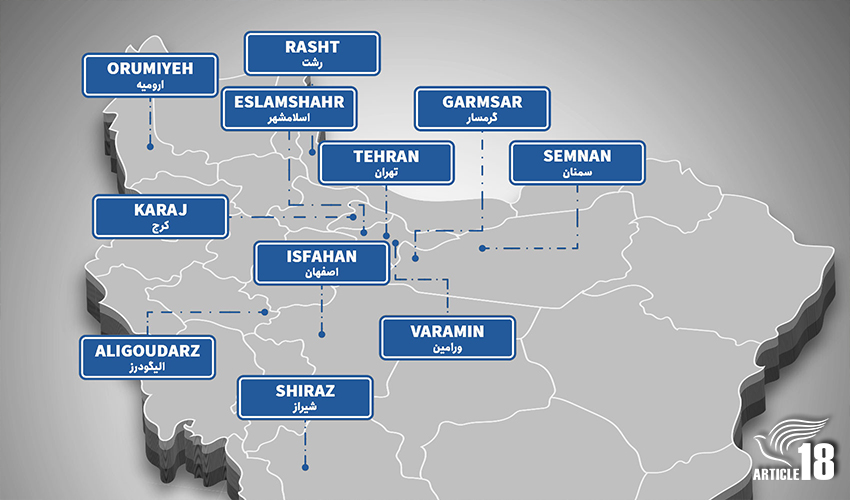

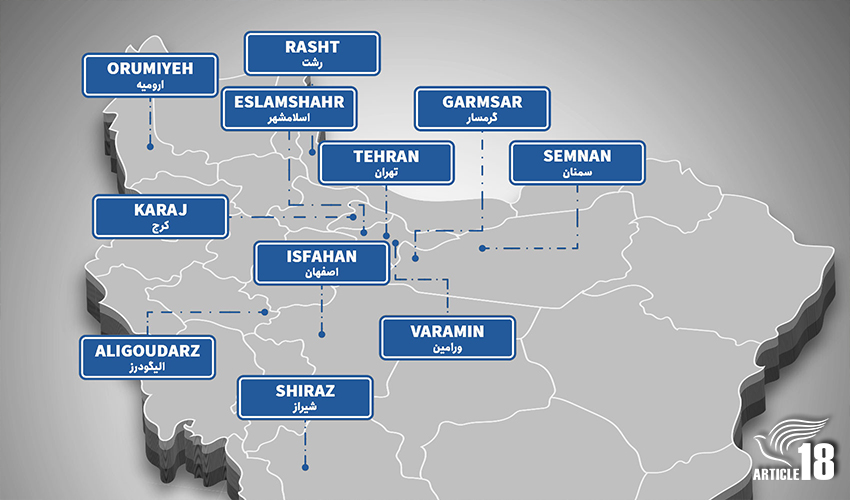

A clearer picture is beginning to emerge of the dozens of arrests of Christians that took place over a seven-week period in June and July, across as many as 11 Iranian cities. Article18 previously reported that over 50 Christians had been arrested in the space of...

by Steve Dew-Jones | 9 Aug 2023 | News

A set of three handwoven rugs by an Iranian Christian asylum-seeker are so impressive and significant that they should be displayed in a national museum, according to the director of the art gallery currently exhibiting the works. Mehdi Jalalaghdamian’s rugs, created...

by Steve Dew-Jones | 8 Aug 2023 | News

A notorious prison outside Tehran is set to be demolished in an attempt by the Islamic Republic to destroy evidence of the crimes against humanity committed there, according to Norway-based NGO Iran Human Rights. Thousands of political prisoners were massacred at the...

by Steve Dew-Jones | 18 Jul 2023 | News

More than 50 Christian converts have been arrested in a rash of new incidents across five Iranian cities over the past seven days, with fears the number could rise much higher as fresh reports keep coming in. At least 51 of those arrested at their homes or...

by Steve Dew-Jones | 17 Jul 2023 | News

An Iranian Christian prisoner of conscience has written about his grief at the loss of his only son and his struggle to understand the reason for his imprisonment, in a letter smuggled out of prison. In the letter, first shared by the Mirror newspaper and now seen by...