This article provides a comprehensive overview of Article18’s joint side event at the UN in Geneva on 23 January, the day before Iran’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) and just one hour before the Islamic Republic’s own side event. You can read further analysis of the contrast between the two events here and watch a full recording of Article18’s event above.

Our event, titled ‘Christians in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Legal Protections vs. Lived Realities,’ included contributions from the UN rapporteur on Human Rights in Iran, Mai Sato, and the Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Nazila Ghanea, as well as representatives from Article18 and co-sponsors CSW and Middle East Concern.

There were also testimonies from Christian convert Amin Afshar-Naderi, who was sentenced to 15 years in prison for his religious faith and activities, and Iranian-Assyrian Christian Dabrina Bet-Tamraz, who was threatened with imprisonment and even execution if she failed to provide information about her parents’ church activities, for which they were also sentenced to a combined 15 years in prison.

Mai Sato

SR Mai Sato begun the event with a recorded video testimony, in which she said the situation of Christians in the Islamic Republic of Iran was “a matter of serious concern that demands our continued attention” and that Iran’s UPR review provided a “timely opportunity to examine the lived realities of Christian communities in Iran”.

Dr Sato said the work of civil society had been “invaluable in documenting human rights violations and maintaining consistent advocacy for religious freedom”.

She added that her predecessors in the role had “raised concerns about the persecution of Christians in the Islamic Republic” through communications to the government in 2011, 2013, 2018, and 2020.

“The violations reported in these communications mirror the very issues that presenters at this event will be discussing today,” she said, including “multiple breaches” of Iran’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Iran ratified in 1975.

“They include the rights to liberty and security, to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief [FoRB], freedom of expression, association, peaceful assembly, physical and psychological integrity, privacy, non-discrimination and the rights of persons belonging to minorities,” she said.

Dr Sato encouraged “all stakeholders to continue sharing information” with her mandate about the situation of Christians and other religious minorities in Iran, saying “your submissions ensure that these issues remain visible on the international agenda”.

The SR concluded by noting that “the distinguished panelists include those who have first-hand experience of these challenges”, adding: “The presence of both civil-society representatives and those directly affected by these violations demonstrates the vital partnership between advocacy organisations and the communities they serve, a partnership that is essential for achieving meaningful change.”

Khataza Gondwe, CSW

CSW’s Khataza Gondwe noted how Iran’s national report, submitted ahead of its UPR review, began by “emphasising that the country’s ‘foundation was not based on ethnic and religious structural conflict’”.

She added that after the 1979 revolution, the new Constitution of the Islamic Republic recognised Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism as religious minorities, “ostensibly allowing [them] to practise their respective rights in personal matters” and stipulating that “all Muslims are duty-bound to treat non-Muslims in conformity with ethical norms and the principles of Islamic justice and equity, and to respect their human rights”.

Article 23 of the Constitution also forbids “the investigation of individuals’ beliefs”, she noted, stating that “no-one may be molested or taken to task simply for holding a certain belief”.

As a state party to the ICCPR and other international legislation protecting the right to FoRB, including to adopt a religion or belief of one’s choice, Dr Gondwe noted that “Iran is under an international legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil this right in full for all within its jurisdiction”.

She also noted that in 2023 Iran’s representative to the Human Rights Council in Geneva had stated in an interactive dialogue with SR Nazila Ghanea that this right should be “respected and protected for all”, and that there was a need to ensure ‘everyone can practice their religion or belief without fear of persecution or prejudice’, and to embrace tolerance and diversity.”

“This sentiment is echoed in the national report for the UPR, which proclaims that ‘religious minorities are permitted to conduct their religious ceremonies freely,’” she added. “However, the realities for religious minorities are somewhat different.”

“In fact, both unrecognised and recognised minority religious and belief communities can experience restrictions when attempting to exercise their right to FoRB,” she said, “arising from official antipathy, societal hostility, and the enactment of laws designed to provide plausible deniability and to lend a figment of legitimacy to abuses of the rights and freedoms of individuals and communities in violation of the ICCPR and even of the national Constitution.”

“Particularly problematic for the Christian community is the fact that their faith is viewed by the authorities through the prism of ethnicity rather than religion,” she said.

“Christians belonging to ethnicities other than the Armenian or Assyrian people groups are viewed with suspicion, as are those from these backgrounds who espouse a more evangelical form of worship.”

Dr Gondwe added that Iran’s national report asserts that there are “approximately 300 churches operating across the country ‘without hinderance’”.

“The number of churches may be a reasonable approximation,” she said. “However, not all were ‘operating without hinderance’ during the reporting period, as several that were closed during the Covid-19 pandemic are yet to be reopened”.

Simon the Zealot Church in Shiraz is one of four remaining Anglican churches in Iran, but none have been permitted to reopen since their forced closure during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Most of the 300-odd churches predate the 1979 Revolution,” she added.

“It would have been more accurate if the Iranian authorities had also divulged how many of the churches are still able to function as worship centres.

“In addition, knowing how many of these churches were constructed after the Islamic Republic was established would serve as an important indicator of the situation of freedom of religion or belief in the country.”

Dr Gondwe noted that Ms Bet-Tamraz will relate “personal testimony that includes the violations, harassment and abuses experienced by her family despite belonging to a recognised [community]”.

Meanwhile, she noted that “the faith of converts to Christianity … who currently constitute the largest proportion of Iran’s Christian community, is not recognised by the authorities”.

Converts’ faith is “also the target of extreme hostility, marking adherents out for intimidation, arbitrary arrests and detentions, physical and psychological mistreatment and lengthy or cyclical convictions and prison sentences”, she said.

Dr Gondwe noted how Iran’s national report also references the controversial amendments to Articles 499 and 500 of the penal code, with the stated “aim of criminalising any spread of hatred, insult and violence against Iranian peoples, divine faiths or Islamic religions”. However, these have “been used to target converts in particular”, she noted, with Article 500 being “the charge most widely levelled against Christians”.

Article 500 further “penalises receiving financial or organisational help from abroad, with a sentence of up to 10 years,” she noted, “negatively impacting donations received by faith communities affiliated with global denominations, and assistance to individuals who are struggling financially.”

Dr Gondwe said the Iranian authorities had, “in a possible effort to contain conversion”, “forced churches to end services in the Persian language, to stop holding meetings on Fridays, which is the national day off, and to not allow converts into their buildings”.

“Only four Persian-language churches remain,” she noted. “Their members are obliged to prove that they were Christians prior to 1979, and the churches are not permitted to take in new members.”

As a result, Dr Gondwe said “Persian-speaking Christians are denied the right to practise their faith in community with others, as private gatherings – or ‘house-churches’ – are subjected to raids by the Ministry of Intelligence, during which attendees are subjected to mistreatment including intimidation, seizure of properties, arrests, excessive bail demands, judicial harassment, and ultimately prison sentences that are often extended by the inclusion of a term of internal exile.”

Dr Gondwe further noted how Mr Afshar-Naderi will “provide testimony of violations experienced as a convert to Christianity, despite guarantees in the ICCPR of the freedom to adopt a religion or belief of one’s choice”.

Iran’s national report also mentions how the Constitution enshrines “equality of the public before the law” and “equal enjoyment of rights by the Iranian people, regardless of ethnicity, colour, race, language, etc,” she said.

“In practice, however, Christians do not enjoy equality before courts and tribunals, nor do they enjoy a fair and public hearing before competent, independent courts of law. Most are tried in Revolutionary Courts that are generally closed to the public and that fail to ensure due process, with many judges passing sentences predetermined by the Intelligence Ministry.

Iran’s report also speaks of “removing discrimination and creating fair opportunities for all”, she said. “However, there have been several instances of the children of converts being unable to access higher education, as their final certificates were withheld for refusing to take Quranic studies in order to progress”.

Dr Gondwe said Iran had also been guilty of a “gross violation of Article 14.7 of the ICCPR, which prohibits the retrial of individuals on charges for which they have been finally convicted or acquitted”, when in January 2022 church leader Abdolreza (Matthias) Ali-Haghnejad, “who had just been released from prison, was re-arrested on charges for which he had been acquitted on appeal in December 2014”.

“The Christian community continues to be monitored and viewed with suspicion,” she concluded. “It has been granted a pseudo-recognition, with provisions in law that do not translate into reality. Unsubstantiated national security-related crimes, along with penalties for taking Communion wine, gathering for prayer, Christmas celebrations, and even a picnic, effectively criminalise normal Christian practices and social activity, while restricting the freedoms of association, expression and the right to manifest their religion or belief, even in private.”

Amin Afshar-Naderi

Christian convert Amin Afshar-Naderi began his testimony by stating that his two arrests – which ultimately led to him spending “about a year in Evin Prison” in Tehran, including 73 days in solitary confinement – “were due to my Christian faith and activities”.

“These arrests happened during the presidency of Hassan Rouhani,” he noted, “who ironically had introduced a ‘Citizen’s Rights Charter’.”

During his detention, Mr Afshar-Naderi says he was “subjected to psychological pressure and threats aimed at forcing me to renounce my Christian faith”.

“To intensify the pressure, I was placed in cells with members of ISIS, intending to make me fear for my life and abandon my beliefs,” he said. “This was despite the fact that Iran’s own Constitution prohibits coercion of beliefs.”

Mr Afshar-Naderi explained how after his first arrest at a Christmas celebration in 2014, he was released on bail “only to be re-arrested again”.

“During my first arrest, security agents took me from the home of a pastor who we were celebrating Christmas with and searched my parents’ home as well,” he said.

Mr Afshar-Naderi said the agents “found a Bible that I had bought from Turkey for my personal study”, which they “seized as evidence of a crime”.

“Later, while in prison, I requested a Bible, explaining that I am a Christian and I had the right to access it,” he said. “While the Quran was readily available to all prisoners, my repeated request for a Bible was denied for a long time, until eventually an intelligence officer mockingly told me: ‘You’re foolish to make such a demand! We brought you here because of the Bible, and now you want us to give you one?’

Mr Afshar-Naderi added that “not only the possession of the Bible but other Christian materials [are] also criminalised”.

“For example, a songbook I used for leading worship was cited in my court verdict as evidence of illegal Christian activities … [and] even used as a justification for accusation of my leadership role in a house-church,” he said.

“In the reports about me, even playing music was described as a tool for misleading others,” he said, “despite the fact that music is universally recognised in Christian worship as a means of glorifying God.”

Mr Afshar-Naderi explained how his second arrest took place while he “at a picnic with Christian friends”.

“When I asked the security agents to present an arrest warrant, instead of presenting the warrant they showed me their gun, sprayed pepper spray in my face, beat me severely, and forced me into their vehicle,” he said.

Mr Afshar-Naderi said he “endured physical and psychological abuse” in detention.

“On multiple occasions, I was verbally and physically humiliated by interrogators and prison guards,” he said. “For example, they used the issue of circumcision—a practice common among Muslims but not Christians—as a way to mock and degrade me sexually.”

Mr Afshar-Naderi said his interrogators “would deny my Christian identity and didn’t want to accept me as a Christian, but at the same time they treated me as impure because of my Christian faith”.

“For instance, when I was being transferring to and from the solitary confinement, even though I was blindfolded and couldn’t see them, the guard would pull on my clothes to avoid physical contact with me,” he said.

Mr Afshar-Naderi added that he wonders whether, “if the doors of our church in Tehran’s Shahrara neighbourhood had not been closed [to us], we would not have had to gather in private homes, and perhaps none of these things would have happened.

“When that church was banned from accepting Persian-speaking Christians, with the cooperation of the Assyrian representative in parliament, the Assyrian pastor of our church [Dabrina Bet-Tamraz’s father] was dismissed. Therefore we were left without options for communal worship, [other than] to gather in our homes.”

He concluded: “My experience is just one example among thousands of Christians in Iran whose ordinary religious activities are criminalised, and their fundamental freedoms are stripped away by the Islamic Republic.”

Dabrina Bet-Tamraz

Dabrina Bet-Tamraz’s parents, Victor and Shamiram, fled Iran in 2020 after being sentenced to a combined 15 years in prison.

Iranian-Assyrian Dabrina Bet-Tamraz began her testimony by retelling a story about a Baha’i who was asked by a judge if he was Baha’i and replied: “What has that to do with my case?”

“The judge said, ‘I’m just personally interested in that.’ Then he replied, ‘Yes, I am a Baha’i,’ and the judge gave him five years in prison just because he’s a Baha’i,” Ms Bet-Tamraz explained.

“The man said: ‘Are we all criminals?’ And the judge said, ‘Yes, you’re all spies.’

“‘So 300,000 Bahais in Iran are spies?’ The judge replied: ‘Yes, they are.’

“‘Even my one-year old nephew?’

“‘Well, maybe not now, but at some point he will be a spy.’

“The Baha’i asked: ‘What if I change my religion, become a Muslim? Am I still a spy?’ And the judge looked at him with anger and shouted: ‘Shut up!’”

Ms Bet-Tamraz said the story resonated with her because “I’ve been arrested, I’ve been interrogated, I’ve been accused of ‘acting against national security’ simply because I was a Christian.”

“I am from a recognised Christian minority in Iran – Assyrian. This means, at least on paper, that we should be protected for our faith, that we should have certain freedoms – to express our faith, to go to church, to practice freely, [but] that cannot be further from truth.”

Ms Bet-Tamraz said that when she was six years old, her parents “taught me the danger of being kidnapped from school” and “never allowed me to come back home alone ever”.

When she was eight, she said she “witnessed the death of pastors and church leaders”.

“I remember with my family, we went to the funeral of one of those pastors who had been murdered for his faith, thinking, ‘When will my dad be buried?’”

“I remember going home to my mum crying because my dad had been arrested and interrogated; our appointments, travel trips being cancelled because Dad is not coming home from prison.

“I remember being told it’s OK if Mum and Dad die; it’s our faith, and we’re going to keep strong, keep holding to our faith.”

Ms Bet-Tamraz said that when she and her brother became teenagers, her parents “taught us how to withstand interrogations, how to not cooperate, what to say and what not to say”.

Then in 2009, at the age of 23, “those lessons came in handy when I was expelled from university, held in a men’s-only detention centre, with no female officer present, being interrogated for my faith”.

“I wasn’t a criminal, I didn’t do anything wrong,” she said. “I simply went to church, was practicing and living my faith.”

“This is not an experience that any Christian, that any human, should endure.”

Ms Bet-Tamraz noted how Article 18 of the ICCPR enshrines the freedom to “share [one’s] faith, express [one’s] faith, and live as who [you] are, [but in Iran] that cannot be further from the truth”.

“I spoke to my father in prison, comforted my mother in hospital when her son was arrested from being at a picnic, together with Amin.

“I said goodbye on the phone to my brother, before he had to submit himself to prison, and I had to stand and look at my family being stripped apart – our dignity, our faith – because of our Christian faith.”

“I’m sure you’ve heard this [said], and I’m sure you’re going to hear this again and again, that ‘Christians are free in Iran’,” she said. “The Iranian representatives are going to say 300 churches are open, and they can practice easily, freely, [but] since 2009 at least 10 Protestant Assyrian [or] Armenian churches have been shut down.

“My faith as an Evangelical, as a Protestant Christian, is considered ‘terrorism’, ‘Zionism’, and ‘an action against national security’.”

“More churches today are restricted and are not allowed to practise freely in their services.”

Ms Bet-Tamraz noted that her father and Mr Afshar-Naderi’s arrests took place 10 years ago, and yet “today, Christians are being arrested during Christmas celebrations for celebrating their Saviour’s birthday.”

“This year alone, more than 40 Christians were arrested,” she noted.

“I was able to flee Iran,” she said. “My parents were able to leave a few years ago, but most of my other family, my brother included, are still home.

“The government is forcing Christians to leave the country, [including] recognised Christians.”

Ms Bet-Tamraz concluded by noting that our latest annual report says “there is no place for ‘unaligned’ Christians in the Islamic Republic of Iran” and that, she said, includes “recognised Assyrian or Armenian Protestant [Christians]”.

Mansour Borji, Article18

Article18’s Mansour Borji began his testimony by saying that the leaked Tehran judiciary files from 2024, which included the cases of over 300 Christians, “serve as undeniable, irrefutable, and unbiased records of human rights abuses”.

“At a time when the Iranian government often dismisses reports of repression as ‘biased’ or ‘fabricated’, these files provide objective evidence that cannot be ignored” and “demand to be documented, studied, and seriously addressed by the international community”, he said.

“The data affirms what countless victims like Amin and Dabrina have bravely testified,” he added. “That the Iranian judiciary and security apparatus operate systematically to suppress the religious freedom of Christians and other minorities.”

The files “expose the depth of the repression … [and] not only outline the tactics used by the Iranian government but also emphasise the urgent need for global action to hold them accountable”, Mr Borji said.

They also reveal that the Iranian judiciary “systematically labels Christians – particularly Persian-speaking evangelicals – as members of ‘deviant sects’ and a ‘security threat’ … a deliberate vilification that is not incidental but a calculated move to justify persecution”.

“The Christians who worship in house-churches are often depicted as agents of foreign powers, while their peaceful religious practices are framed as attempts to undermine the Islamic Republic – a rhetoric, rooted in unfounded paranoia, [that] fosters an atmosphere of hostility that legitimises repression.”

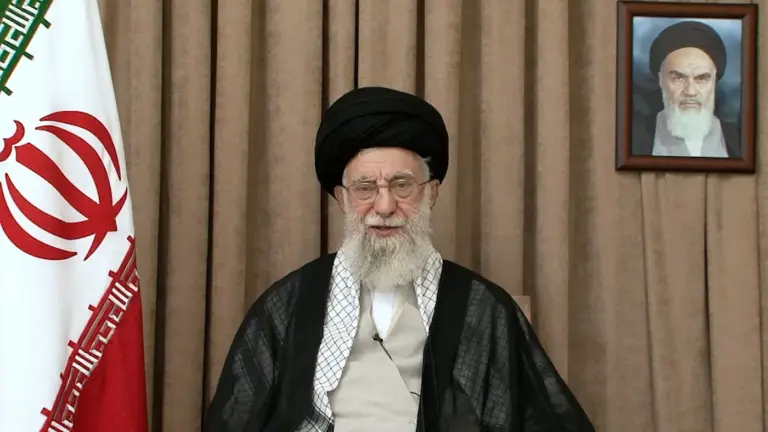

Mr Borji noted how, “in just over an hour, in this place and in this very room, a delegation of the Iranian government will present a different version of the situation of Iranian Christians.

“An Iranian-Assyrian parliamentary representative will probably say we have 300 churches that ‘operate unrestrictedly’. I am here to say that this is far from the truth.

“The representative [Sharli Envieh] who would want us to believe these statements are true has himself said on the record that evangelical churches are ‘repugnant to us’ and ‘completely rejected by our churches’.”

In this magazine, Sharli Envieh (pictured) refers to the promotion of Christianity as “detestable”.

Mr Borji noted that Mr Envieh “is on record, both written and also on video, and the printed magazine – which I happen to have a copy of here – the front cover of a magazine printed in Iran that quotes him saying: ‘Evangelical Christianity’, or ‘promoting Christianity’, is a ‘detestable’ or ‘hated’ thing.

“We cannot have somebody who considers a majority of the Christian population and a global belief [shared by Christians] ‘hateful’ to speak as a representative for all Christians.

“Evangelical churches are not hateful. They don’t want to undermine national security. In fact, they seek the best of their country and other nations.”

Another “alarming revelation” from the leaked files, Mr Borji said, is “the treatment of Bibles and Christian literature as contraband and evidence of a ‘crime’”, as was also seen in 2023 when one-third of all arrests of Christians involved “charges related to distributing Bibles or evangelistic materials”.

“These actions highlight the Iranian government’s fear of religious diversity,” he said. “Religious diversity not in a sense that you would show the tourists historical churches and buildings that are restricted or closed to most Christians – especially to those who speak the national language of Persian. Not only 300, you could have 1000, but if they’re restricted, that is not a sign of religious diversity. They’re just buildings for touristic purposes.”

True religious diversity, Mr Borji said, as enshrined under Article 18 of the ICCPR, “includes the right to adopt a religion or belief of one’s choice, and freedom to manifest their religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching. And no-one shall be subject to coercion which would impair his freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice”.

Mr Borji said the findings in the leaked judiciary files offer “a stark reminder of the Iranian government’s systematic denial of religious freedom”, which should be “not just a matter for human rights advocates” but “a matter of global conscience”.

“We must ensure that these abuses are not met with silence,” he concluded. “As members of civil society and the international community, we have a duty to amplify the voices of the oppressed, document their stories, and demand accountability from those who commit these violations.”

Nazila Ghanea

The UN’s SR on FoRB began her testimony by stating that Article18’s latest annual report shows how a “distinction is being drawn by the Islamic Republic of Iran between ethnic Christians and others, especially converts”, despite the fact that Christian converts are “numerically the largest Christian community in Iran”.

“As we all know, they are not recognised by the state, and are frequently targeted by the authorities,” she said.

Dr Ghanea noted the heavy sentencing of Christians in 2024, with “96 Christians sentenced to a combined 263 years in prison, 37 years in internal exile and some $800,000 in fines” – “a colossal sum everywhere, but especially in Iran, in the context of extreme economic austerity”.

And beyond the figures, Dr Ghanea said “there are, of course, the human stories that one needs to focus in on in order to even try to grasp the terrible human cost”.

Dr Ghanea focused on the case of Ebrahim Firouzi, “who tragically died at the age of 37 back in February 2024”.

“He had originally been arrested in 2011, when he would have been around 24 years old, for involvement in a house-church, possession of Bibles and ‘promoting Christianity’,” the SR noted.

“Having spent six years in prison, he was then exiled for two years, more than 1,000 miles from his home.

“His body was found in his flat by his brother, and let’s just spend one moment to think of the tragic pain of that discovery.

“Heavy bails, heavy sentences, refusal of prison leave, which runs counter even to the Iranian prison law, followed by distant exile on release … are replicated across a number of the cases that the report logs.”

The SR said that for “compelling reasons like this”, her next report will focus on “FoRB and the prohibition of torture and other inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”.

A number of other cases in the report “can rightly be recognised as being violative also of the prohibition of torture, inhuman and degrading treatment”, she said.

Dr Ghanea notes that the report “observes the stark statistic that over 70% of the charges against Christians in 2024 were filed under the amended Article 500” of the penal code.

“The report further draws from the leaked files from the Tehran district judiciary that the charges used most frequently against Christians related to ‘propaganda against the Islamic state’, under Article 500, followed by membership or leadership of ‘anti-security groups’ under Articles 498 and 499.”

“And for ‘anti-security groups’, read ‘house-churches’,” she said.

Dr Ghanea said “these and other provisions of the Islamic Penal Code [IPC] effectively serve to criminalise key protections of freedom of religious belief under international human rights law”.

“The amended articles 499 and 500 were added to the IPC in order to define punishments for ‘perverse sects’,” she noted. “Sects, groups or societies considered to have ‘deviant educational or propagation activities contradictory or detrimental’ – allegedly – ‘to the holy religion of Islam’.

“Financing or supporting these groups aggravates the crime and increases the punishment, so under 499 bis, the punishment is five years, [but] if there has been receipt of financial or organisational help from outside Iran, this is doubled to 10 years’ imprisonment. And similarly for Article 500 bis.”

Dr Ghanea noted that “the property of the leaders or financial providers of such groups can and are readily confiscated for the benefit of the Iranian Treasury”.

“And [Article18’s] report details that in the past year, amended Article 500 was used by judges to issue confiscation orders for Christian properties and vehicles in at least two cases.”

The SR concluded by saying that the report “is called ‘The Tip of the Iceberg’, and that would be 10% of the iceberg above the surface of the water and 90% beneath… [but] I suspect we’re actually seeing so much less than 10% of the sufferings endured over the past year, despite the hard work and good presentation of [the] report.

“Let’s just reflect on the pain of internal exile, the separation of children from parents, the lives lost, the anguish of mothers, the incredulity of suffering, interrogation, and criminalisation for mere exercise of freedom of religion or belief.

“This and so much more just cannot be captured in words and infographs, but to the extent that it can this report is highly informative, and I warmly thank you for it.”

Patrick Conway, Middle East Concern

The final speaker, Patrick Conway from MEC, noted that the annual report and joint recommendations ahead of Iran’s UPR both concern “State-led rights violations against Christians in Iran”, including for the Iranian authorities to:

- “respect and protect the human rights of everyone in Iran … including to FoRB … and the right to peaceful assembly … regardless of people’s religious, ethnic or linguistic background or status.”

- “release all Christians who are detained in connection with peaceful religious activities – whether they are detained connected with investigations or criminal charges, or serving a prison sentence.”

- “allow Christians of all religious, linguistic and ethnic backgrounds to gather freely and collectively”, “ceas[ing] the criminalisation of house-church organisation and membership, allow[ing] all Christians to simply have places where they can gather together for peaceful religious purposes, including in the Persian language.”

- “return places of worship and other properties and material confiscated from Christians in connection with peaceful faith practices.”

- “permit the reopening of those churches forcibly closed in connection with the attendance of Christian converts and holding services in the Persian language,” such as the Assemblies of God Central Church in Tehran.

- “permit the reopening of four Anglican churches closed during the Covid-19 pandemic for public-health reasons … [which] unlike other places of worship that were closed during the pandemic … have yet to be permitted to reopen, even now.”

- “afford recognition to and protect the human rights of all Christians, and not only ethnic Armenians, Assyrians and the small community of expatriate Christians who are afforded limited protections.”

- “amend Article 13 of the Iranian Constitution to conform with international law, including as to Article 18 ICCPR … [such that] protections be expanded to people of all faiths and beliefs.”

- “guarantee access to legal counsel of their choosing, including for Christians charged with alleged ‘national security’- related crimes.”

- “cease to unjustly prosecute and imprison Christians for peaceful faith-related activities, including under trumped-up allegations concerning ‘national security’ and ‘propaganda against the State’.”

- “grant access to the country to UN officials who may request it, such as [Dr Sato] … allowing such officials unhindered access to assess compliance with international human rights law.”

Mr Conway noted that at least 18 Christians were still in prison “under sentences related to their peaceful faith-related activities” at the end of 2024, including Iranian-Armenian Hakop Gochumyan, who has “now not seen his family for the last two Christmases”, and Mina Khajavi, “a lady in her sixties, who has metal plates fitted in one of her ankles, who suffers from arthritis and is struggling with pain”.

Mina Khajavi.

“In prison, she is not receiving the medication or medical care she requires,” Mr Conway noted, and “she has been in prison for over a year.”

Mr Conway noted that the churches that have been closed by the authorities in recent years “faced more and more restrictions on operations, including days on which they could or could not operate, and demands to provide lists of church members, until being finally closed in connection with holding Persian language services”.

“Presbyterian churches, for example, remain open to worshippers but with significant restrictions,” he said. “Only Christians who are of Armenian and Assyrian backgrounds are permitted by the authorities to attend these churches, and these churches are not permitted to have services in Persian.”

Mr Conway said “the Christians who are targeted on account of their faith mean no harm to Iran, its authorities or anybody. They simply wish to be permitted to practice their faith collectively, in a wholly peaceful manner, and to do so in their mother tongue, Persian, without facing arrest, prosecution and lengthy terms of imprisonment.

“It is asked that the authorities consider that house-churches are not political vehicles and are in no way subversive, or a threat to national security. Christian converts gather in homes because they are precluded by the State from establishing churches or attending public churches.”

He added: “Iran is unquestionably a country of great beauty, and so rich in history and culture. And common to those who are forced to flee Iran due to State-led rights violations and fear of targeting and prison sentences, is that they love their country and really wish to remain there.”

Mr Conway encouraged the UPR Working Group to “raise these rights violations during the Universal Period Review concerning Iran … and afford due weight to these serious and long-standing rights violations that are well documented”.

“And … that these violations be consistently raised through United Nations Mechanisms, including the Human Rights Council, with the authorities in Iran and afforded due weight in reports and other dialogue; including of office holders under relevant special procedures of the Human Rights Council.”

Mr Conway also asked the wider international community to “raise and highlight these rights violations through the UN and otherwise in dialogue with the Iranian authorities”.

And third countries hosting Iranian Christians who fled Iran and have applied for asylum “to assess [their] applications with due diligence, recognising the well-founded fears of Christians of experiencing serious rights violations if forced to return to Iran”.

Q&A

Claire Denman, CSW

“All of these recommendations are in line with Iran’s commitment to the ICCPR and other international covenants,” noted CSW’s Claire Denman, introducing the Q&A and noting that the Islamic Republic had accepted just four of 30 recommendations related to FoRB during the last UPR cycle.

“So that’s a really stark reminder of Iran’s lack of commitment and lack of interest in upholding the right to freedom of religion or belief in law and in practice,” she said, encouraging the recommendations to be consistently raised “through both the UPR and also through other mechanisms in the UN system”.

“We do encourage you, as states and as civil society representatives here today to consistently be raising these recommendations, even if you feel like they’re falling on deaf ears,” she said.

“It is important that we continue to hold the Iranian authorities to account, and that we continue to ensure that the spotlight is being shone on these violations.”

The aim of the event, she said, was “both to help highlight some of these concerns, narratives and trends” but also to encourage advocates “to keep going. Do not give up. Do not lose hope”.

“Please keep using the UPR as a tool, and whichever recommendations you raise, we encourage you to include freedom of religion or belief recommendations, because they are such a touchstone recommendation that incorporate so many other issues – the right to freedom of expression, assembly, association as examples.”

She added: “We’re under no illusions as well that the UPR process is somewhat limited in this scope, and that’s because it’s a peer to peer review process, where at the end of the day there’s little recourse for unimplemented or rejected recommendations.“

Q. Aside from the UPR, what other accountability mechanisms should be used?

Khataza Gondwe, CSW

Responding to Ms Denman’s question, Dr Gondwe stressed the importance of “continuously raising human rights in dialogue”.

“In every dialogue, in every arena, wherever there’s engagement with Islamic Republic, there should be discussion on improving their human rights record,” she said. “People shouldn’t shy away from this.”

Dr Gondwe also championed the use of targeted Magnitsky sanctions against individuals, noting that several Iranian officials have already been sanctioned but that the sanctions may need to be “renewed” to ensure other individuals “who are just as egregious, or even worse than the ones that have already been sanctioned” are not missed.

Finally, Dr Gondwe suggests that the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights could help by encouraging Iran to “amend laws so that they actually meet with international standards”.

Q. How far does the experience of other unrecognised minorities align with that of unrecognised Christians? And what has been the impact of these violations on the size of the Christian community?

Mansour Borji, Article18

Responding to a question from Open Doors International’s Anna Hill, Mr Borji referenced Dabrina Bet-Tamraz’s story about the Baha’i individual, and noted how the Bahai International Community uses the hashtag #OurStoryisOne to highlight the similarities among different minorities.

“But the issue of religious freedom is not just a matter of religious minorities,” he added.

“I think that denial of this right to religious minorities is a symptom of a greater pain to the whole population; that you would not know that this right is being taken away from you unless you exercise it by expressing your freedom of religion, to choose and adopt a religion, to not have a religion, to express it publicly. And that’s when you realise there is no majority or minority. Everyone’s right to religious freedom is denied.”

Mr Borji added that the impact on the Christian community of the violations has been “many, many of them leaving the country”.

“For instance,” he said, “the Assyrian population probably in 1979 was between 20,000-40,000; now the number has declined significantly, so much so that the representative in the parliament has less than 2,000 votes to get into the parliament. So that shows the decline.”

Patrick Conway, Middle East Concern

Mr Conway added his own response, calling on nation states and others who engage with Iran “to do their research, to use the tools that are available, including this latest annual report – and the detailed joint stakeholders report of Article18, CSW, Middle East Concern and Open Doors … to equip themselves with the knowledge that they need to engage in a meaningful manner with Iran …

“You’ll find copies of those reports on the organisation’s websites, where you’ll find a wealth of further information on Iran, particularly on Article18’s website,” he said, such that “when the answers [those who engage with Iran] receive just don’t add up – if they’re going to be fobbed off, so to speak, with answers which suggest that things are rosy and that Christians and people of other faiths and none enjoy freedoms in Iran – through having this information we are able to see that those things just don’t add up.

“So I would ask for engagement in a full and frank manner and in a manner where answers that don’t add up aren’t simply accepted, and then the state will move on; [but] that they use this information to press for further answers as to these questions and so to make progress as to these issues, because this is an ongoing, long-standing problem of rights violations against people of minority faiths, and I think if if there is to be progress, then a real, full, frank and robust dialogue needs to take place.”

Q. Would the victims like to say anything else in anticipation of the Islamic Republic’s forthcoming event and UPR statements?

Dabrina Bet-Tamraz

Responding to a question from Article18’s news director, Steve Dew-Jones, Ms Bet-Tamraz said that while she was “curious” to see what will be said, she’d heard the expected responses “quite a lot in the past 20, 30, 40, years of my life” and “I don’t think I would be hearing anything new that I don’t know”.

“For as long as I can remember, I’ve heard lies, accusations,” she said, “and I don’t believe this will stop.”

“It’s simply up to you to decide what’s true and what’s not. I believe you will hear a lot of facts and a lot of numbers. Please fact-check them. Please ask questions. Ask for more details.

And take notes of what we have said and just compare [the two] so you can know who’s lying, who’s telling the truth.”

Amin Afshar-Naderi

Mr Afshar-Naderi added that he had “lived almost 30 years of my life” in Iran, and “10 of those years as a Christian”, and had “heard repeatedly [their] claims, while what I experienced in reality was very different”.

“So I’m very interested to hear what they have to say, and I’m hopeful to see some changes, some real changes and evidence of a real change; that their treatment of religious minorities and, in general, the population has differed from what I experienced,” he said. “I remain hopeful to hear such things.”

Claire Denman, CSW

Ms Denman concluded the meeting by saying she hoped those who had attended “leave us today with a better understanding of the situation for both recognised and unrecognised Christian minority groups in Iran, and information with which to counter the narratives of the Islamic Republic of Iran officials that Christians in the country face no restrictions on their enjoyment to freedom of religion or belief”.

“We also hope that you’re equipped with a better appreciation of the importance of nuanced and targeted recommendations for both recognised and unrecognised Christian communities in Iran.

“And we hope that this event stands to complement the event hosted by the Baha’i International Community earlier this week, as these abuses also affect members of other religious minorities.”

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks